Abstract

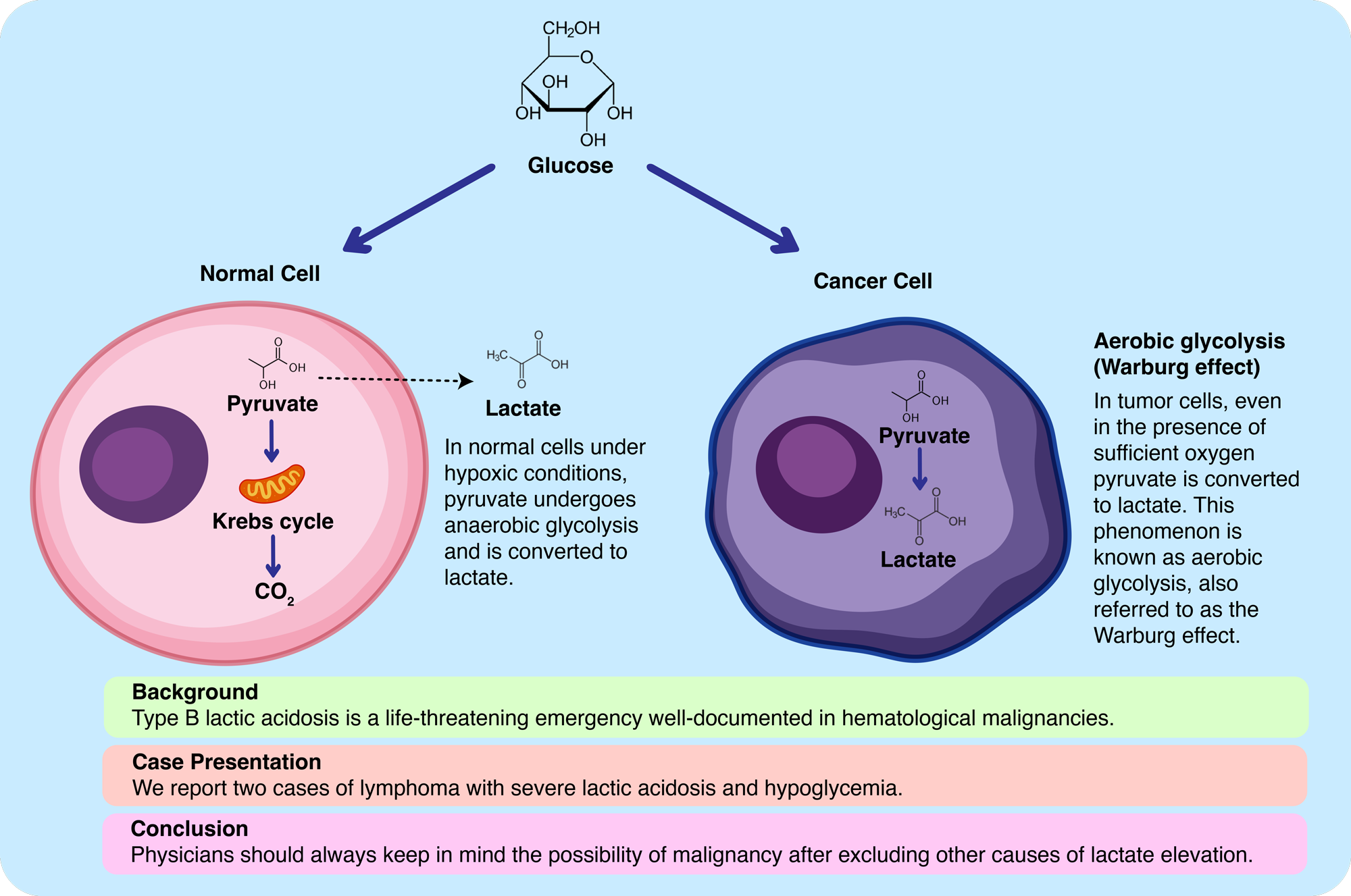

Type B lactic acidosis is a rare life-threatening condition associated with hematological malignancies. This condition is of great clinical importance because it requires rapid diagnosis and treatment. Its association with malignancies is based on the Warburg effect. The Warburg effect is a condition in which tumor cells prefer glycolysis over oxidative phosphorylation for energy production, which may lead to severe lactic acidosis.

Here, we report two cases of patients who presented with severe lactic acidosis and hypoglycemia that could be explained by Warburg phenomenon, were followed up in the intensive care unit and subsequently diagnosed with lymphoma. We aim to contribute to the literature on Warburg phenomenon by detailing the rapid and successful management of these cases.

Keywords: type B lactic acidosis, hypoglycemia, hematologic malignancy, intensive care

Introduction

Hyperlactatemia is defined as a serum lactate level exceeding 2.0 mmol/L without acidemia (1). Lactic acidosis is characterized with a pH of <7.35 accompanied by lactate elevation. The etiology of lactic acidosis needs to be clarified early because it carries an ominous prognosis (2). There are two types of lactic acidosis; Type A being the most common one associated with hypoxia or hypoperfusion and Type-B lactic acidosis which is rare compared to type-A and is associated with liver disease, vitamin B1 deficiency, alcoholism, medications such as metformin and adrenalin, and malignancies (3). Lactic acidosis developing due to the high turnover of malignant cells is called the Warburg effect (4). Otto Warburg first described this phenomenon in the 1920s, and it is mainly since tumor cells prefer the glycolytic pathway even in the presence of oxygen (4,5).

Herein, we present 2 cases admitted with hypoglycemia and lactate elevation and subsequently diagnosed with lymphoma. In these cases, we observed that serum lactate decreased gradually and hypoglycemia resolved after chemotherapy initiation. We also report this a literature review, emphasizing the relationship between the Warburg phenomenon and malignancy.

Patients and Methods

We utilized the retrospective medical records of two patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) who developed type-B lactic acidosis and hypoglycemia as a complication of hematologic malignancy. Literature review was conducted by searching “PubMed” and “Google Scholar” in English literature from January 2002 to June 2022 using ‘’Warburg effect and lymphoma’’ and ‘’type-B lactic acidosis, hypoglycemia and lymphoma’’ keywords.

Case Series

Case 1

A 19 years-old female was admitted to the emergency department at 22 weeks of pregnancy presenting with fever, abdominal pain, and generalized fatigue. Her physical examination revealed generalized lymphadenopathy. Laboratory examination showed normocytic anemia (hemoglobin (Hb) 6.8 g/dL, mean corpuscular volume (MCV) 86 fL), neutrophilic leukocytosis (leukocyte count 26x103/μL, neutrophil count 18.2x 103/μL), lymphopenia (lymphocyte count 0.79x103/μL) and elevated inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein 35 mg/dL [normal <0.5mg/dL] and erythrocyte sedimentation rate 61 mm/h). Lactic acidosis (pH 7.27, bicarbonate 9 mmol/L, and lactate 8 mmol/L) and asymptomatic hypoglycemia (glucose level 55 mg/dL) were noted. There was no coagulopathy, encephalopathy and jaundice. Sepsis was suspected and broad-spectrum antibiotics were started. Infectious work-up, including blood and urine cultures, have not revealed any meaningful results. Fluid resuscitation and thiamine (vitamin B1) were also administered to the patient. She was intubated due to severe metabolic acidosis. The patient became anuric and continuous renal replacement therapy was started. She was extubated after metabolic acidosis recovered and her bicarbonate level returned to normal range. However, serum lactate levels did not normalize despite optimal treatment. Even with 25 cc/h 30% dextrose infusion was administered, serum glucose levels remained low. Spontaneous abortion occurred at the 22nd week of gestation.

After the abortion, the patient was evaluated by computerized tomography (CT). Numerous lymph nodes were reported in cervical tomography, suggesting lymphoproliferative disease. A cervical lymph node biopsy was performed. As infectious causes were excluded, 6 mg dexamethasone therapy was started with the initial diagnosis of lymphoproliferative disease. In a few days, clinical recovery was observed. Cervical lymph node biopsy pathology revealed “anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-positive anaplastic large cell lymphoma”, stained positive for CD30, CD4, CD2, ALK, and granzyme. Small cells were stained positive for CD20, CD3, CD8, and CD5 and negative for CD56. Ki67 index was found as 70%.

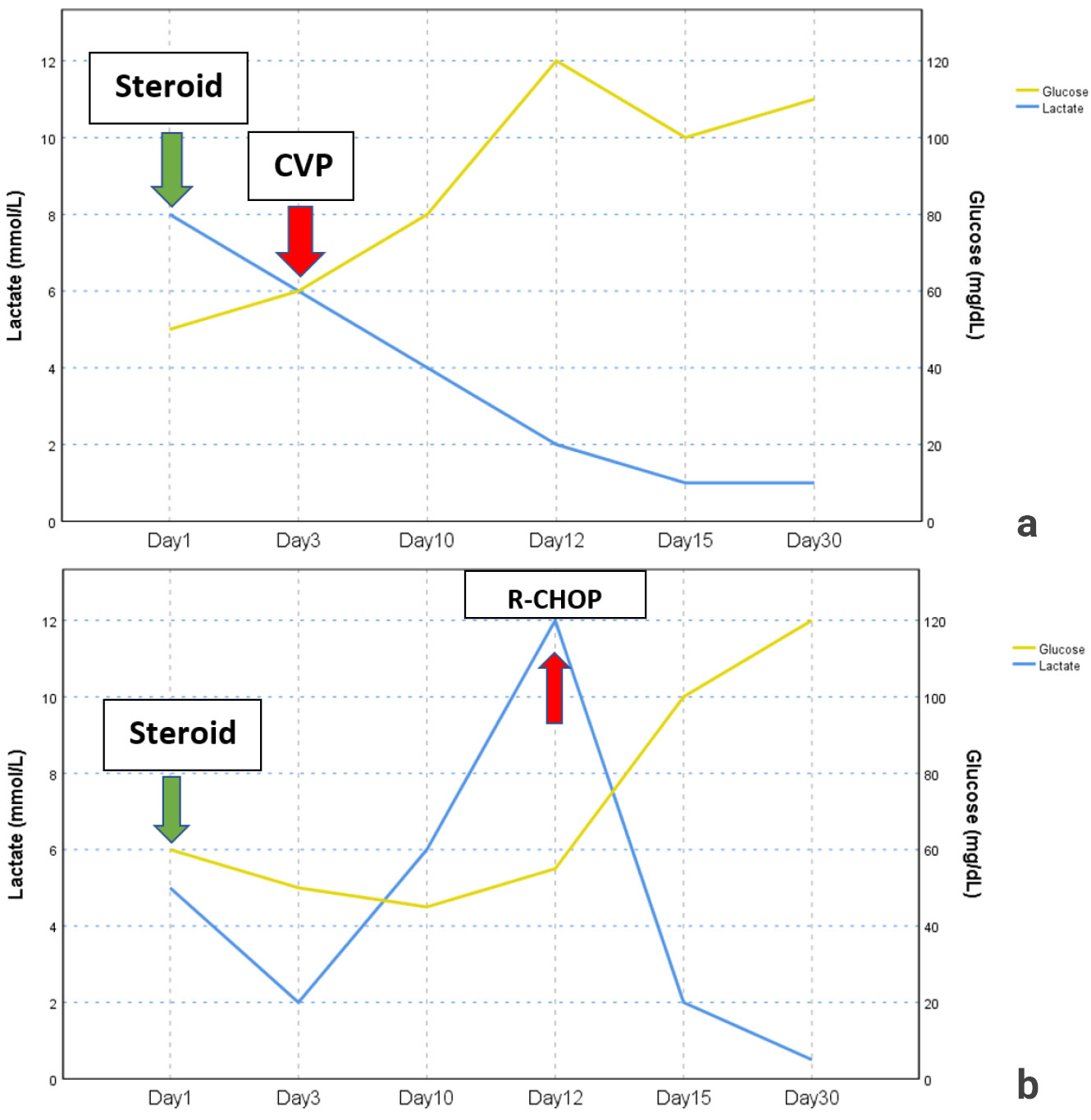

The Cyclophosphamide, Vincristine, Prednisone chemotherapy protocol was initiated and after that resistant hypoglycemia resolved, and lactate levels returned to normal range (Figure 1a). The patient received multiple chemotherapy regimens. However, she passed away due to septic shock approximately 1 year after the diagnosis.

Case 2

A 19 years-old female was admitted to the emergency department with nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Her vital signs were within normal range except hypotension. Physical examination showed epigastric tenderness with moderate ascites. Lung sounds were diminished at the subzone of the lungs, and a bilateral 2-3 positive pretibial edema was observed.

Laboratory assessment revealed microcytic anemia (Hb 9.9 g/dL, MCV 72 fL), neutrophilic leukocytosis (neutrophil count 11.2x103/μL), lymphopenia (0.21x103/μL), thrombocytosis (426x103/μL), elevated inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein 6.2 mg/dL) and pancreatic enzymes (amylase 357 U/L [normal 28-100 U/L], pancreatic amylase 270 U/L [normal 8-53 U/L], lipase 425 U/L [normal <67 U/L]). There was no coagulopathy, encephalopathy and jaundice.

CT scan of the abdomen performed at the admission to the emergency department revealed diffuse thickening of the head of the pancreas and an appearance compatible with periaortitis. With the preliminary diagnosis of sepsis, broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy was initiated as the lactate level raised to 12.0 mmol/L during the patient’s follow-up. One-gram methylprednisolone was commenced with the initial diagnosis of IgG4-related disease. There was no improvement in lactate levels despite optimal fluid resuscitation, antibiotic therapy and thiamine replacement. Infection workup, including blood and urine cultures, were negative. During her ICU stay, multiple hyperemic nodular lesions appeared in whole body with approximately 3x3 cm diameter in which the biggest lesion was seen on her abdominal skin, and punch biopsies were obtained from there.

After the methylprednisolone dose had started to be reduced to 48 mg, her abdominal pain recurred, and pancreatic enzymes and lactate levels increased. Therefore, the methylprednisolone dose was increased again to 64 mg/day. Despite oral intake and administration of IV dextrose solution, the patient had persistent hypoglycemia (lowest level 41 mg/dL). Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was performed to exclude intrahepatic cholestasis and duodenal biopsy was obtained. The pathology of both skin and duodenal biopsy revealed high-grade diffuse large B cell lymphoma. The skin biopsy specimen stained positive for CD20, BCL6 and negative for CD3, CD5, Cyclin D1, CD23, MUM1 and CD10. The proliferative index (Ki67) was found over 90%. Duodenal biopsy stained positive for CD20, BCL6 and negative for MUM1 and CD10 . The proliferative index (Ki67) was found as 90%. The biopsy results excluded the diagnosis of IgG4-related disease. The Rituximab, Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin, Vincristine, Prednisone chemotherapy protocol was immediately initiated. After initiation of chemotherapy, resistant hypoglycemia resolved and serum lactate level decreased dramatically (Figure 1b). After she had received 5 cycles of chemotherapy, febrile neutropenia developed. She passed away due to septic shock approximately 1 year after initial diagnosis.

Literature review

There have been 30 cases of Warburg effect associated malignancies reported in the last 21.5 years that we have reviewed (Table 1). Twenty-three cases had lymphoma, three had multiple myeloma, two had chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), one with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and one with adenoma of unknown origin. Diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) was the most common cause (46%) among the defined cases. Twenty-one of the cases were male. The median age was 58 (min-max, 19-79 years). The median lactate level was 13.5 mmol/L (min-max, 3.24-29). Hypoglycemia was reported in 43% of cases. Eight of the cases were followed in the ICU. Twenty-three of 30 patients had received treatment (22 received chemotherapy and one received only steroid treatment). Others could not receive chemotherapy due to deterioration in their clinical status, refusal of treatment or postmortem diagnosis. The overall mortality was 76%, whereas it was reported that mortality was 69% in patients who received chemotherapy.

| ICU: Intensive care unit, M: Male, NR: Not reported, MM: Multiple myeloma, VAD: Vincristine, Adriamycin and Dexamethasone, NK/T-cell lymphoma: Natural killer/T cell lymphoma, CHOP: Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine (or oncovin) and prednisone, AML: acute myelocytic leukemia, F: Female, FL: Follicular lymphoma, DLBCL: Diffuse large B cell lymphoma, CLL: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia, R-CHOP: Rituximab, Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine (or oncovin) and prednisone, VRD-PACE Bortezomib, dexamethasone, cisplatin, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and etoposide, EPOCH: etoposide, epirubicin, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, and prednisolone, VR-CAP: Bortezomib, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone, EPOC-RR: Rituximab, etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin, R-EPOCH: Rituximab, etoposide, doxorubicin, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, and prednisone, CV: Cyclophosphamide and vincristine. | ||||||||||

| Table 1. Case reports associated with type B lactic acidosis and lymphoma in the literature | ||||||||||

| No |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 11 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 12 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 13 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 14 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 15 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 16 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 17 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 18 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 19 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 21 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 22 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 23 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 24 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 25 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 26 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 27 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 28 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 29 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 30 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Discussion

Current case reports demonstrated that lactate elevation and hypoglycemia might be associated with occult lymphomas in critically ill patients admitted to ICU, which has been described as so-called “Warburg phenomenon”. Lymphomas are a heterogeneous group of malignancies of the lymphoid system. The majority of lymphomas are non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) ranging from low-grade to rapidly growing and high-grade histology (6). NHL usually presents with painless lymphadenopathy, whereas some may have accompanying systemic symptoms. The definite diagnosis is made by histopathological examination of the appropriate and adequate biopsy specimen (7). It is not always possible to diagnose with appropriate lymph node sampling in patients with rapidly progressive clinics, eventually it may be fatal if not diagnosed and treated. High lactate levels and lactic acidosis during lymphoma are associated with poor prognosis. Mortality is more than 80% when Warburg effect is present (8). Although the best treatment for patients with malignancies who develop type-B lactic acidosis is not clear yet, chemotherapy seems to be the most appropriate first choice (9). The Warburg Effect is visually summarized in Figure 2.

The first stage of oxidative phosphorylation is known as glycolysis and takes place in the cytoplasm. As a result of glycolysis, 2 molecules of pyruvic acid are formed and converted to acetyl-coenzyme A (acetyl-co A). Acetyl-co A enters the Krebs cycle in the mitochondria. By entering the electron transport chain (ETC) in the inner membrane of the mitochondria, 36 adenosine-three-phosphate (ATP) is obtained at the end and a water molecule is also formed. In the absence of oxygen, pyruvate was not converted to Acetyl-co A, but transformed to lactic acid, known as anaerobic glycolysis. In this way, the net energy balance is only two ATP molecules (10). On the other hand, in cancer cells, the glycolytic pathway is preferred even in the presence of oxygen, which is known as aerobic glycolysis or the Warburg effect (11). As a result, only 2 ATP is obtained. More glucose must be consumed in cancer cells for the same amount of energy. This mechanism why cancer cells prefer a less efficient pathway has not fully been understood yet. The plausible hypothesis is that cancer cells use the formed carbon chains derived from aerobic glycolysis for amino acids, nucleotides, and lipid synthesis which are significant for cancer cell proliferation (12). In addition, an acidic environment is created with the activation of the glycolytic pathway in cancer cells, which paves the way for tumor invasion with local toxicity (13). Warburg effect also forms the basis of the fluorodeoxyglucose and positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) system, which is based on increased glucose metabolism and utilized for the diagnosis and follow-up of several tumors (14).

Remarkably, 2 patients in this report were younger than the other reports. Although most of the cases in the literature were male, 2 of our cases were female. The pre-treatment lactate levels were 8 and 12.6 mmol/l, and hypoglycemia was present in both of our cases. One of our cases was diagnosed with DLBCL and the other one with ALK+ lymphoma in the ICU. Lactic acidosis and hypoglycemia disappeared with appropriate early chemotherapy and both of our patients received chemotherapy and passed away 1 year after admission.

We know that lactic acidosis can have numerous causes. Septic shock is the most common etiology of lactic acidosis in ICUs (15). We could not rule out septic shock in these patients and started fluid replacement and antibiotic therapy. We also administered thiamine. Despite this, the persistence of lactic acidosis and the deterioration of the clinical condition of the patients in addition to the presence of hypoglycemia despite continuous glucose infusion directs the potential role of the Warburg effect.

In both of our patients, imaging could not be performed with PET-CT, as it was deemed necessary to make a quick diagnosis and to start the treatment as quick as possible. Biopsy was planned as a result of CT imaging. There was no hepatic failure in the differential diagnosis of hypoglycemia. Since both of our patients were under steroid treatment, cortisol levels were not tested. Unfortunately, patients were not tested for insulin and c-peptide levels for the differential diagnosis of hypoglycemia.

Conclusions

We wanted to emphasize the relationship between the Warburg effect and lymphoma, which has been known for years. Clinicians should always keep in mind the possibility of malignancy after excluding other potential causes of lactate elevation. Lactic acidosis and hypoglycemia could resolve with rapid initiation of efficient chemotherapy in chemo-sensitive tumors.

Ethical approval

This study has been approved by the Hacettepe University Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee (approval date: 09.12.2025, number: SBA25/991).

Source of funding

The authors declare the study received no funding.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Fall PJ, Szerlip HM. Lactic acidosis: from sour milk to septic shock. J Intensive Care Med. 2005;20:255-71. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885066605278644

- de Groot R, Sprenger RA, Imholz ALT, Gerding MN. Type B lactic acidosis in solid malignancies. Neth J Med. 2011;69:120-3.

- Foucher CD, Tubben RE. Lactic Acidosis. In: statPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Potter M, Newport E, Morten KJ. The warburg effect: 80 years on. Biochem Soc Trans. 2016;44:1499-505. https://doi.org/10.1042/BST20160094

- Pascale RM, Calvisi DF, Simile MM, Feo CF, Feo F. The warburg effect 97 years after its discovery. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12:2819. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12102819

- Shankland KR, Armitage JO, Hancock BW. Non-hodgkin lymphoma. Lancet. 2012;380:848-57. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60605-9

- Armitage JO, Gascoyne RD, Lunning MA, Cavalli F. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Lancet. 2017;390:298-310. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32407-2

- Bakker J, Nijsten MW, Jansen TC. Clinical use of lactate monitoring in critically ill patients. Ann Intensive Care. 2013;3:12. https://doi.org/10.1186/2110-5820-3-12

- Friedenberg AS, Brandoff DE, Schiffman FJ. Type B lactic acidosis as a severe metabolic complication in lymphoma and leukemia: a case series from a single institution and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2007;86:225-32. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0b013e318125759a

- Granchi C, Bertini S, Macchia M, Minutolo F. Inhibitors of lactate dehydrogenase isoforms and their therapeutic potentials. Curr Med Chem. 2010;17:672-97. https://doi.org/10.2174/092986710790416263

- Devic S. Warburg effect - a consequence or the cause of carcinogenesis? J Cancer. 2016;7:817-22. https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.14274

- Liberti MV, Locasale JW. The warburg effect: how does it benefit cancer cells? Trends Biochem Sci. 2016;41:211-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2015.12.001

- Gatenby RA, Gillies RJ. Why do cancers have high aerobic glycolysis? Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:891-99. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc1478

- Pauwels EK, Sturm EJ, Bombardieri E, Cleton FJ, Stokkel MP. Positron-emission tomography with [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose. Part I. Biochemical uptake mechanism and its implication for clinical studies. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2000;126:549-59. https://doi.org/10.1007/pl00008465

- Ferreruela M, Raurich JM, Ayestarán I, Llompart-Pou JA. Hyperlactatemia in ICU patients: incidence, causes and associated mortality. J Crit Care. 2017;42:200-05. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2017.07.039

- Ustun C, Fall P, Szerlip HM, et al. Multiple myeloma associated with lactic acidosis. Leuk Lymphoma. 2002;43:2395-97. https://doi.org/10.1080/1042819021000040116

- He YF, Wei W, Sun ZM, et al. Fatal lactic acidosis and hypoglycemia in a patient with relapsed natural killer/T-cell lymphoma. Adv Ther. 2007;24:505-09. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02848772

- Ruiz JP, Singh AK, Hart P. Type B lactic acidosis secondary to malignancy: case report, review of published cases, insights into pathogenesis, and prospects for therapy. ScientificWorldJournal. 2011;11:1316-24. https://doi.org/10.1100/tsw.2011.125

- Elhomsy GC, Eranki V, Albert SG, et al. “Hyper-warburgism,” a cause of asymptomatic hypoglycemia with lactic acidosis in a patient with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:4311-16. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2012-2327

- Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Whitaker-Menezes D, Valsecchi M, et al. Reverse warburg effect in a patient with aggressive B-cell lymphoma: is lactic acidosis a paraneoplastic syndrome? Semin Oncol. 2013;40:403-18. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.seminoncol.2013.04.016

- Tang P, Perry AM, Akhtari M. A case of type B lactic acidosis in multiple myeloma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2013;13:80-82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clml.2012.07.005

- Buppajarntham S, Junpaparp P, Kue-A-Pai P. Warburg effect associated with transformed lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31:999.e5-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2013.01.038

- Sia P, Plumb TJ, Fillaus JA. Type B lactic acidosis associated with multiple myeloma. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62:633-37. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.03.036

- El Imad T, El Khoury L, Geara AS. Warburg’s effect on solid tumors. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2014;25:1270-77. https://doi.org/10.4103/1319-2442.144266

- Yun S, Walker CN, Vincelette ND, Anwer F. Acute renal failure and type B lactic acidosis as first manifestation of extranodal T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014:bcr2014205044. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2014-205044

- Kuo CY, Yeh ST, Huang CT, Lin SF. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma presenting with type B lactic acidosis and hemophagocytic syndrome. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2014;30:428-29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kjms.2013.10.001

- Claudino WM, Dias A, Tse W, Sharma VR. Type B lactic acidosis: a rare but life threatening hematologic emergency. A case illustration and brief review. Am J Blood Res. 2015;5:25-29.

- Wahab A, Kesari K, J Smith S, Liu Y, Barta SK. Type B lactic acidosis, an uncommon paraneoplastic syndrome. Cancer Biol Ther. 2018;19:101-04. https://doi.org/10.1080/15384047.2017.1394550

- Arif H, Zahid S, Kaura A. Persistent lactic acidosis: thinking outside the box. Cureus. 2018;10:e2561. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.2561

- Mejia M, Perez A, Watson H, et al. Successful treatment of severe type B lactic acidosis in a patient with HIV/AIDS-associated high-grade NHL. Case Reports Immunol. 2018;2018:9093623. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/9093623

- Talwalkar PG. Severe and persistent hypoglycemia with lactic acidosis in an elderly lady with type 2 diabetes mellitus and lymphomaleukemia: a rare case report. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2019;13:648-50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2018.11.037

- Hamada T, Kaku T, Mitsu S, Morita Y, Ohno N, Yamaguchi H. Lactic acidosis and hypoglycemia in a patient with gastric diffuse large B-Cell lymphoma due to the warburg Effect. Case Rep Oncol. 2020;13:1047-52. https://doi.org/10.1159/000509510

- Al Maqrashi Z, Sedarous M, Pandey A, Ross C, Wyne A. Refractory hyperlactatemia and hypoglycemia in an adult with non-hodgkin’s lymphoma: a case report and review of the warburg effect. Case Rep Oncol. 2021;14:1159-67. https://doi.org/10.1159/000517658

- Goyal I, Ogbuah C, Chaudhuri A, Quinn T, Sharma R. Confirmed hypoglycemia without whipple triad: a rare case of hyper-warburgism. J Endocr Soc. 2020;5:bvaa182. https://doi.org/10.1210/jendso/bvaa182

- Hwang CS, Hwang DG, Aboulafia DM. A clinical triad with fatal implications: recrudescent diffuse large B-cell non-hodgkin lymphoma presenting in the leukemic phase with an elevated serum lactic acid level and dysregulation of the TP53 tumor suppressor gene - a case report and literature review. Clin Med Insights Blood Disord. 2021;14:2634853521994094. https://doi.org/10.1177/2634853521994094

- Looyens C, Giraud R, Neto Silva I, Bendjelid K. Burkitt lymphoma and lactic acidosis: a case report and review of the literature. Physiol Rep. 2021;9:e14737. https://doi.org/10.14814/phy2.14737

- Salcedo Betancourt JD, Garcia Valencia OA, Becerra-Gonzales VG, et al. Severe type-B lactic acidosis in a patient with bilateral renal Burkitt’s lymphoma. Clin Nephrol Case Stud. 2021;9:49-53. https://doi.org/10.5414/CNCS110123

- Wang C, Lv Z, Zhang Y. Type B lactic acidosis associated with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and the Warburg effect. J Int Med Res. 2022;50:3000605211067749. https://doi.org/10.1177/03000605211067749

Copyright and license

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is properly cited.