Abstract

Introduction: Sepsis, defined by Sepsis-3 as a life-threatening organ dysfunction due to infection, has high mortality rates worldwide. Early diagnosis and treatment are challenging due to its heterogeneous nature. Identifying predictive factors is crucial for improving outcomes. This study aims to analyze sepsis patients in the intensive care units (ICU) of Lokman Hekim University Ankara Hospital.

Methods: A retrospective analysis of 400 patients diagnosed with sepsis (Sepsis-3 criteria) between April 2020 and April 2024 was conducted. Data included demographics, clinical parameters, laboratory results, comorbidities, treatments and outcomes.

Results: The median age was 81 years (range: 21–101), with 214 patients (53.5%) aged 80 years and above. Hypertension (56.5%), diabetes mellitus (38.3%), and coronary artery disease (26.5%) were common comorbidities. Lactate levels were significantly higher in non-survivors (2.7 vs. 1.7 mmol/L, p=0.006). Non-survivors had higher Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores, while Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) scores were higher in survivors. Invasive mechanical ventilation was required in 98.6% of non-survivors. Overall ICU mortality was 86.5%. The total culture positivity rate was 65.5%, with blood cultures positive in 32.8% of cases. Staphylococcus epidermidis, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Klebsiella pneumoniae were common blood isolates. In respiratory cultures, K. pneumoniae and A. baumannii predominated, while E. coli and Candida species were frequent in urine cultures. However, culture positivity in blood, urine, or respiratory samples did not significantly impact mortality. Logistic regression identified age, APACHE II score, serum procalcitonin level, and Mean arterial pressure (MAP) as independent mortality risk factors.

Conclusion: Key predictors of mortality in sepsis include age, APACHE II score, procalcitonin, and MAP. Therefore, early identification and tailored interventions may improve outcomes in sepsis management. Further research is needed to refine prognostic models.

Keywords: sepsis, prognosis, mortality, critical care

Introduction

According to the Sepsis-3 definition, sepsis is a life-threatening condition caused by an abnormal host response to infection, leading to organ dysfunction (1). Mortality from sepsis shows significant regional variation; in Europe, the rate is approximately 41%, whereas in the United States, it is around 28.3% (2).

An epidemiological study examining sepsis across intensive care units in Turkey revealed that 15.8% of patients had infections without Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS), while 10.8% had infections accompanied by SIRS. Additionally, the study showed 17.3% of patients had severe sepsis without shock, whereas 13.5% had septic shock. When the researchers regrouped according the Sepsis-3 criteria, they found that 6.9% of patients were in septic shock and this subgroup had a high mortality rate (75.9%) (3). In another study carried out in Turkey, when culture results were categorized, Gram-negative bacteria were identified in 48% of cases, Gram-positive bacteria in 15%, and fungi in 8%, and 29% of patients had negative cultures. The reported in-hospital mortality rate was 51% (4). The heterogeneous nature of sepsis revealed in these studies is the key factor that complicates early diagnosis and treatment planning (5).

Due to its heterogeneous nature, identifying predictive factors in sepsis can help clinicians intervene early, improve patient outcomes, and reduce mortality rates. (6). Although studies on predictive biomarkers in sepsis have increased in recent years, identifying effective predictive factors for sepsis management remains challenging due to the limitations of these studies. In a study investigating the predictive value of the Lactate/Albumin ratio, it was found to be more predictive of 28-day mortality in critically ill sepsis patients than a single lactate measurement, and was recommended as a strong prognostic marker independent of the initial lactate level (7). While systematic reviews and meta-analyses highlight the effectiveness of machine learning models in predicting the onset of sepsis, the variability across studies complicates the evaluation of results; nevertheless, these models provide alternatives to traditional scoring systems. Therefore, there remains a need for systematic reporting and clinical research to further investigate this area (8).

The aim of the study was to review the demographic, characteristics and comorbidities effect on outcomes.

Methods

This study was designed retrospectively and carried out at the intensive care units (ICUs) at Lokman Hekim University Ankara Hospital between 01.04.2020 and 01.04.2024. Ethical approval was obtained from the Lokman Hekim University Scientific Research Ethics Committee (approval date: 01/03/2024, number: 2024/75).

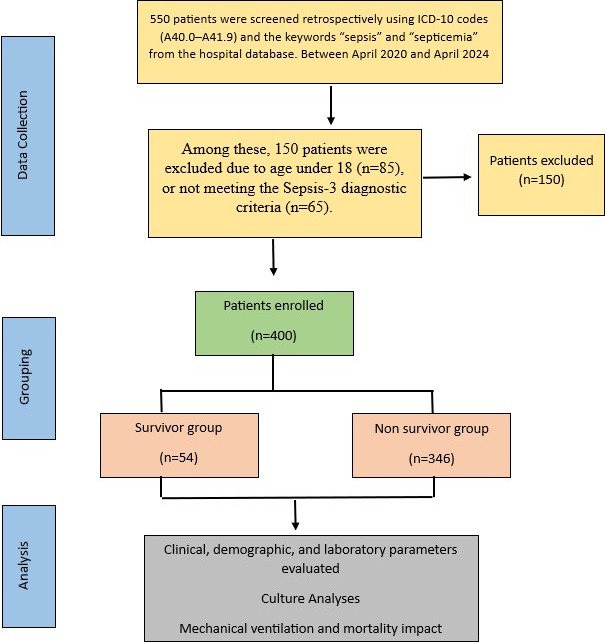

The patient’s data were obtained from the hospital’s database system and intensive care follow-up form. When searching hospital system, International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision (ICD 10) codes (A40.0-A41.9), the key words “sepsis and septicemia” were used. For the patient’s selection, 2016 Sepsis-3 diagnostic criteria were used for the definitions of sepsis, septic shock and patient selection (1). The patients having clinical and laboratory findings compatible with sepsis according to the sepsis-3 criteria and aged over 18 years old were included in the study. Exclusion criteria were defined as being under 18 years old and pregnant. The selection criteria of the patients are shown in the flow chart in Figure 1.

The demographic information of the cohort, such as age and gender, Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) score, the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) Score at admission, serum levels of lactate, procalcitonin (PCT), C-reactive protein (CRP), leukocyte, lymphocyte, platelet, albumin, D-dimer, comorbidities, identified infection sources, documented pathogens and antimicrobial resistance results, need for mechanical ventilation and its duration, mortality were recorded. Clinical and laboratory parameters impact on mortality were analyzed. For analysis, patients were grouped retrospectively based on ICU survival status as survivors and non-survivors. The primary outcome of the study was ICU mortality. Secondary outcomes included the evaluation of demographic, clinical, and laboratory parameters as potential predictors of mortality.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis of the study data was performed using IBM SPSS (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) version 27.0. The normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, histograms, and skewness-kurtosis coefficients. Continuous variables were presented as median (minimum–maximum) due to non-normal distribution, while categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. For the comparison of continuous variables between two groups, the Mann-Whitney U test was used. Categorical variables were compared using the Chi-square test. Binary logistic regression analysis was performed to identify independent risk factors for mortality. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 400 patients diagnosed with sepsis and septic shock were included in this study. Of the patients, 48.3% were male. The median age was 81 years (range: 21-101) and 214 cases were aged 80 years and over. Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of patients. The most common comorbidities were hypertension (56.5%), diabetes mellitus (38.3%), and coronary artery disease (26.5%). However, no significant relationship was found between the presence of comorbid diseases and mortality (p>0.05).

| Data are presented as number (%) for categorical variables and median (minimum–maximum) for continuous variables. | ||||

| Table 1. The total number of patients with sepsis patients included in the study, along with their sociodemographic profiles and associated chronic conditions. | ||||

| Characteristic |

|

|

|

|

| Male (No, %) |

|

|

|

|

| Age (median, min, max) |

|

|

|

|

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension |

|

|

|

|

| Diabetes Mellitus |

|

|

|

|

| Coronary Artery Disease |

|

|

|

|

| Heart Failure |

|

|

|

|

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

|

|

|

|

| Stroke |

|

|

|

|

| Chronic Kidney Disease |

|

|

|

|

Initially, 550 patients were screened retrospectively using ICD-10 codes (A40.0–A41.9) and the keywords “sepsis” and “septicemia” from the hospital database. Among these, 150 patients were excluded due to age under 18 (n=85), or not meeting the Sepsis-3 diagnostic criteria (n=65). No patients were excluded due to incomplete data during chart review. The remaining 400 patients were then divided into two groups based on ICU survival status: survivors (n=54) and non-survivors (n=346).

Clinical and laboratory findings

When evaluating the clinical and laboratory parameters of the patients, significant differences were observed between survivors and non-survivors. Parameters such as heart rate, mean arterial pressure (MAP), PCT, CRP, and CRP/albumin ratio (CAR) had statistically significant effects on mortality (p<0.001, Table 2). The lactate levels were found to be 1.7 (0.5-93) mmol/L in survivors and 2.7 (0.2-113) mmol/L in non-survivors, with this difference being statistically significant (p:0.006). However, no significant difference was detected in terms of other parameters such as neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and albumin levels (p>0.05).

|

MAP; Mean Arterial Pressure, PCT; Procalcitonin, WBC; White Blood Cell count, PLT; Platelets, CRP; C-reactive Protein, CAR: C-Reactive Protein/Albumin Ratio, NLR; Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio. Data are presented as number (%) for categorical variables and median (minimum–maximum) for continuous variables. |

||||

| Table 2. Analysis of the clinical characteristics and laboratory parameters of sepsis patients. | ||||

| Variable |

|

|

|

|

| Sepsis |

|

|

|

|

| Septic shock |

|

|

|

|

| Heart rate (bpm) |

|

|

|

|

| MAP (mmHg) |

|

|

|

|

| PCT (ng/mL) |

|

|

|

|

| WBC (x109/L) |

|

|

|

|

| PLT (x109/L) |

|

|

|

|

| CRP (mg/L) |

|

|

|

|

| Albumin (g/dl) |

|

|

|

|

| CRP/Albumin (CAR) |

|

|

|

|

| Neutrophils (x109/L) |

|

|

|

|

| Lymphocytes (x109/L) |

|

|

|

|

| NLR |

|

|

|

|

| Lactate (mmol/L) |

|

|

|

|

| Positive Culture |

|

|

|

|

| Positive Respiratory Secretion Culture |

|

|

|

|

| Positive Blood Culture |

|

|

|

|

| Positive Urine Culture |

|

|

|

|

Culture analyses

The total culture positivity rate was 65.5%, and the blood culture positivity rate was 32.8%. The most frequently isolated bacteria from blood cultures were Staphylococcus epidermidis (19.08%), Acinetobacter baumannii (11.45%), and Klebsiella pneumoniae (10.69%). In respiratory secretion cultures, the most frequently isolated microorganisms were K. pneumoniae (27.41%), A. baumannii (20.00%), and Candida species (11.85%). In urine cultures, the most commonly isolated pathogens were E. coli (27.41%), K. pneumoniae (20.00%), and Candida species (23.70%) (Table 3). The presence of at least one positive culture in any sample did not significantly affect mortality. Similarly, having a positive blood, urine, or respiratory secretion culture did not have a statistically significant impact on mortality when assessed separately (p>0.05, Table 2). There was no statistically significant difference between survivors and non-survivors in terms of blood, respiratory secretion, or urine culture positivity (p>0.05). Although total culture positivity was higher in non-survivors (67.3% vs. 53.7%), the difference was borderline significant (p=0.050).

|

* Citrobacter, Hafnia alvei, Serratia, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, Providencia rettgeri, Pantoea agglomerans, Cedecea lapagei, Corynebacterium striatum, Raoultella ornithinolytica ** Staphylococcus simulans, Streptococcus agalactiae, Enterococcus faecium, Streptococcus spp., Aerococcus viridans Data are presented as number (%). |

|||

| Table 3. Distribution of microorganisms isolated from patients with sepsis. | |||

| Microorganisms |

|

|

|

| Gram-negative bacteria | |||

| Klebsiella pneumoniae |

|

|

|

| Acinetobacter baumannii |

|

|

|

| Escherichia coli |

|

|

|

| Enterobacter spp. |

|

|

|

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

|

|

|

| Others* |

|

|

|

| Gram-positive bacteria | |||

| Staphylococcus epidermidis |

|

|

|

| Staphylococcus aureus |

|

|

|

| Enterococcus spp. |

|

|

|

| Streptococcus haemolyticus |

|

|

|

| Staphylococcus capitis |

|

|

|

| Staphylococcus hominis |

|

|

|

| Others ** |

|

|

|

| Fungi | |||

| Candida spp. |

|

|

|

| Total |

|

|

|

Outcomes

The median duration of ICU stay for the patients was 8 days (range:1-114). There was no statistically significant difference in the length of hospital stay between survivors and non-survivors (p:0.228). The need for invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) was significantly higher in non-survivors (98.6%) compared to survivors (20.4%) (p<0.001). The duration of IMV was significantly longer in non-survivors (median 4 days) than in survivors (median 0 days, p<0.001). In terms of disease severity criteria such as APACHE II and SOFA scores, non-survivors had significantly higher values, while GCS scores were significantly higher in survivors. (p<0.001, Table 4).

| APACHE II; Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II, SOFA; Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, GCS; Glasgow Coma Scale, IMV; Invasive Mechanical Ventilation. | ||||

| Table 4. Evaluation of outcomes among patients with sepsis. | ||||

| Variable |

|

|

|

|

| Length of stay (days) |

|

|

|

|

| Invasive MV Requirement |

|

|

|

|

| IMV/days |

|

|

|

|

| APACHE II |

|

|

|

|

| SOFA |

|

|

|

|

| GCS |

|

|

|

|

In logistic regression analysis, age (p:0.039), APACHE II score (p:0.004), PCT (p:0.007), and MAP (p<0.001) were identified as independent risk factors for mortality (p<0.05, Table 5).

| APACHE II; Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II, SOFA; Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, GCS; Glasgow Coma Scale, WBC; White Blood Cell count, CRP; C-reactive Protein, CAR; C-Reactive Protein/Albumin Ratio, NLR; Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio, IMV; Invasive Mechanical Ventilation, MAP; Mean Arterial Pressure, PCT; Procalcitonin. | ||||||||

| Table 5. A comprehensive list of variables identified as potential predictors for ICU mortality, derived from univariate binary logistic regression, alongside the independent ICU mortality predictors established through multivariate binary logistic regression analysis. | ||||||||

| Variables |

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Age |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| APACHE II |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| SOFA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| GCS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| PCT |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| WBC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Platelets |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| CRP |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Albumin |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| CRP/Albumin (CAR) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Neutrophils |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Lymphocytes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| NLR |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Lactate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| IMV Days |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MAP |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Among the 400 cases included in the study, 346 patients (86.5%) died in the ICU, with a mortality rate of 86.5%. The mortality rates were significantly higher in patients diagnosed with septic shock when compared to those diagnosed with sepsis (p<0.001).

Discussion

The study findings highlight critical factors influencing patient outcomes and provide insights into the epidemiology, clinical characteristics and microbial landscape of sepsis in a tertiary care setting. Age, APACHE II score, PCT levels and MAP emerged as independent predictors of mortality. The previous studies show the role of severity scoring systems and biomarkers in prognosticating sepsis outcomes. Elevated APACHE II scores and low MAP underscore the need for aggressive hemodynamic monitoring and management in critically ill patients. Recent studies have further supported the use of multimodal biomarker combinations and advanced scoring systems to refine mortality predictions in sepsis patients (9-12).

Despite SOFA scores being found to be high in the non-survivor group in our study, it was not found to be an independent risk factor for mortality in the analyses performed. However, when the literature is examined, prospective studies on lactate are important in the management of sepsis. In addition, a prospective study identified factors such as decreased mobility, delayed sepsis diagnosis in the emergency department, higher SOFA scores at admission and inappropriate antimicrobial treatment as key risk factors for ICU mortality (13). Another meta-analysis revealed that each one-point increase in the SOFA score was associated with a 2.4 increase in 90-day mortality in patients with septic shock, and that elevated SOFA scores were linked to higher 30-day mortality in both sepsis and septic shock. These studies underscore the prognostic role of the SOFA score in sepsis (14). Furthermore, both MAP and elevated heart rate at admission were found to significantly increase the likelihood of ICU mortality, as indicated by the analysis of these clinical parameters. These findings underscore the importance of early identification and comprehensive clinical assessment in improving outcomes for sepsis patients (13).

Lactate levels and the lactate/albumin ratio, as markers of tissue hypoperfusion, are valuable indicators for investigating poor prognosis in sepsis. Advances in omics-based technologies are enabling the characterization of sepsis endotypes, and pave the way for integrating molecular biomarkers with clinical parameters to improve outcome predictions (9–11). Although lactate was not found to be an independent risk factor for mortality in our study, recent research suggests that lactate plays a key role in sepsis, not only as a disease marker but also by promoting increased inflammation. These findings indicate that lactate may serve as a valuable target for both the diagnosis and treatment of sepsis (15).

Current studies have suggested that biomarkers such as NLR and plasma lactate levels are strong predictors of 28-day mortality in sepsis patients. A study by Liu et al. (16) reported that both NLR and lactate levels are independently associated with poor outcomes in sepsis. However, the lack of significant differences in other markers suggests that combining multiple biomarkers may provide more reliable predictive value. This notion aligns with findings from other studies, which support the use of multimodal biomarkers to enhance the sensitivity and specificity of sepsis prediction models. These findings indicate that plasma lactate levels are a significant biomarker in the prognosis of sepsis and suggest that this parameter could be more widely utilized in clinical practice. However, the lack of a significant association between NLR and mortality in our study implies that the prognostic value of NLR may vary depending on the patient population, clinical context or stage of sepsis. Considering the limitations of assessments based on a single biomarker, combining reliable biomarkers such as lactate with NLR and other potential indicators could enable the development of models that better predict sepsis outcomes. This approach may facilitate the development of individualized treatment plans and help reduce mortality rates.

Emerging biomarkers such as IL-6 and circular RNAs are showing promise in enhancing diagnostic and prognostic accuracy (11,12). Even though it is not possible to examine blood tests that are not routinely used in retrospective analyses, future studies should investigate the clinical utility of jointly evaluating biomarkers and explore how such combined approaches can be optimized in the diagnosis and management of sepsis.

The most commonly isolated microorganisms, K. pneumoniae and A. baumannii, reflect the challenges posed by multidrug-resistant organisms in ICU settings. The high prevalence of Gram-negative bacteria underscores the importance of antimicrobial stewardship programs to curb resistance rates. Literature highlights the global burden of antimicrobial resistance in sepsis management, further emphasizing the need for rapid diagnostic techniques (9,12,17). In our study, the absence of a significant relationship between positive or negative results in respiratory secretion, blood, and urine cultures and mortality (p>0.05) suggests that other clinical and patient-related factors may play a more decisive role in influencing mortality.

In our study, non-survivors required IMV significantly more often than survivors. Timely and effective management strategies of respiratory failure including the judicious use of mechanical ventilation and other therapeutic modalities, are essential for mitigating the risk of mortality. These interventions not only improve patient outcomes by stabilizing respiratory function, but also underscore the need for proactive care to escalation of respiratory compromise. Studies have demonstrated that early recognition and intervention in cases of respiratory distress are essential for improving survival rates and reducing the need for more invasive treatments (10,11). Consistent with the literature and our findings revealed a higher IMV in the non-survivor group.

In our study, the mortality rate appears to be much higher than the rates typically reported in the literature. According to the literature, mortality in sepsis is generally high, and increases further in cases of septic shock (4,7,13,14,18,19). The higher mortality rate in our cohort may be attributed to several factors that differentiate this study population from those in other studies. The higher mortality rate observed in our study may be related to the severity of the patients included in our cohort. It is likely that our patients had more advanced stages of sepsis or septic shock, or were affected by multiple underlying conditions, which are known to increase mortality risk. In comparison, studies with lower mortality rates may have focused on patients with less severe forms of sepsis or those who received early, aggressive interventions.

Additionally, the heterogeneous nature of septic shock (characterized by multi-organ failure, hemodynamic instability, and metabolic disturbances) may have contributed to the high mortality rate observed in our cohort. Although survival rates for septic shock have improved in recent years with advancements in medical treatment, the prognosis remains poor in many cases, particularly in patients with delayed diagnosis or treatment (1).

Study limitations

Retrospective studies, which rely on pre-existing data, are susceptible to certain limitations, such as selection bias and the accuracy of available clinical information. In this study, for instance, the inclusion of patients who were already critically ill and the use of historical clinical records may have made it more challenging to account for all potential influencing factors.

Additionally, as the data were collected from a single center, the findings may not be generalizable to other settings or populations. Furthermore, incomplete or missing data for certain parameters could introduce bias, potentially affecting the accuracy and reliability of the results.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study identified, age, APACHE II score, PCT and MAP as independent risk factors for ICU mortality. The findings shown the importance of early recognition, individualized management and a multidisciplinary approach in improving sepsis outcomes. The study underscores the heterogeneity of sepsis and the need for tailored therapeutic approaches. Early identification of high-risk patients using validated scoring systems and biomarkers is crucial to optimize outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Prof. Dr. Mehmet Doganay from Prof. Dr. Mehmet Doğanay from the Department of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology, Lokman Hekim University, for critical suggestions and review.

Ethical approval

This study has been approved by the Lokman Hekim University Scientific Research Ethics Committee (approval date: 01.03.2024, number: 2024/75).

Source of funding

The authors declare the study received no funding.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315:801-10. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.0287

- Levy MM, Artigas A, Phillips GS, et al. Outcomes of the surviving sepsis campaign in intensive care units in the USA and Europe: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:919-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70239-6

- Baykara N, Akalın H, Arslantaş MK, et al. Epidemiology of sepsis in intensive care units in Turkey: a multicenter, point-prevalence study. Crit Care. 2018;22:93. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-018-2013-1

- Sipahioğlu H, Onuk S, Dirik H, Bulut K, Sungur M, Gündoğan K. Evaluation of non-intensive care unit acquired sepsis and septic shock patients in intensive care unit outcomes. Erciyes Med J. 2022;44:161-6. https://doi.org/10.14744/etd.2021.47427

- van Amstel RB, Kennedy JN, Scicluna BP, et al. Uncovering heterogeneity in sepsis: a comparative analysis of subphenotypes. Intensive Care Med. 2023;49:1360-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-023-07239-w

- Liu Q, Zheng HL, Wu MM, et al. Association between lactate-to-albumin ratio and 28-days all-cause mortality in patients with acute pancreatitis: a retrospective analysis of the MIMIC-IV database. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1076121. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.1076121

- Shin J, Hwang SY, Jo IJ, et al. Prognostic value of the lactate/albumin ratio for predicting 28-day mortality in critically ILL sepsis patients. Shock. 2018;50:545-50. https://doi.org/10.1097/SHK.0000000000001128

- Fleuren LM, Klausch TLT, Zwager CL, et al. Machine learning for the prediction of sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:383-400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-019-05872-y

- Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Aschenbrenner AC, Bauer M, et al. The pathophysiology of sepsis and precision-medicine-based immunotherapy. Nat Immunol. 2024;25:19-28. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-023-01660-5

- Peters van Ton AM, Kox M, Abdo WF, Pickkers P. Precision immunotherapy for sepsis. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1926. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.01926

- He RR, Yue GL, Dong ML, Wang JQ, Cheng C. Sepsis biomarkers: advancements and clinical applications-a narrative review. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:9010. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25169010

- Luka S, Golea A, Vesa SC, Leahu CE, Zaganescu R, Ionescu D. Can we improve mortality prediction in patients with sepsis in the emergency department? Medicina (Kaunas). 2024;60:1333. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60081333

- Vucelić V, Klobučar I, Đuras-Cuculić B, et al. Sepsis and septic shock - an observational study of the incidence, management, and mortality predictors in a medical intensive care unit. Croat Med J. 2020;61:429-39. https://doi.org/10.3325/cmj.2020.61.429

- Bauer M, Gerlach H, Vogelmann T, Preissing F, Stiefel J, Adam D. Mortality in sepsis and septic shock in Europe, North America and Australia between 2009 and 2019- results from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2020;24:239. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-02950-2

- Yang K, Fan M, Wang X, et al. Lactate promotes macrophage HMGB1 lactylation, acetylation, and exosomal release in polymicrobial sepsis. Cell Death Differ. 2022;29:133-46. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41418-021-00841-9

- Liu Y, Zheng J, Zhang D, Jing L. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and plasma lactate predict 28-day mortality in patients with sepsis. J Clin Lab Anal. 2019;33:e22942. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcla.22942

- Slim MA, van Mourik N, Bakkerus L, et al. Towards personalized medicine: a scoping review of immunotherapy in sepsis. Crit Care. 2024;28:183. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-024-04964-6

- Amrein K, Zajic P, Schnedl C, et al. Vitamin D status and its association with season, hospital and sepsis mortality in critical illness. Crit Care. 2014;18:R47. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc13790

- Alabay S, Ulu Kilic A, Cevahir F, Alp E, Doğanay M. Evaluation of clinical course and outcomes of severe sepsis and septic shock in elderly patients. J Clin Pract Res. 2024;46:84-91. https://doi.org/10.14744/cpr.2024.57966

Copyright and license

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is properly cited.