Abstract

Background: Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is a significant complication in intensive care unit (ICU) patients, driven by polypharmacy and critical illness. This study aimed to investigate the incidence, clinical characteristics, implicated agents, and outcomes of DILI in ICU patients.

Methods: This retrospective, cross-sectional study included patients with abnormal liver function tests admitted to a tertiary ICU between October 2023 and October 2024. Patients with viral, alcoholic, autoimmune, tumor-related, or other non-drug-related liver diseases were excluded. Data on demographics, clinical scores, medications, and outcomes were analyzed. Causality was assessed using the RUCAM scale.

Results: Among 475 ICU patients, 16 cases (9.89%) were identified as DILI. The mean age was 47.1±23.6 years; 43.8% were female. Antibiotics were the most frequently implicated agents (62.5%), followed by anticoagulants and antipsychotics. The predominant pattern of liver injury was hepatocellular (81.3%). DILI developed approximately 9.5±5.2 days after ICU admission. Mortality among DILI patients was 56.3%, emphasizing the critical nature of hepatotoxicity in this population.

Conclusion: DILI in ICU patients is strongly associated with anti-infectives, particularly β-lactam antibiotics, and predominantly manifests as hepatocellular injury. High mortality underscores the need for vigilant liver monitoring, timely withdrawal of suspected drugs, and a multidisciplinary approach where clinical pharmacists can play a key supportive role. DILI may contribute to morbidity and mortality in critically ill patients, highlighting the importance of early recognition and proactive management.

Keywords: Drug-induced hepatotoxicity, critically ill patients, Hepatocellular injury, Polypharmacy

Introduction

Drug-induced hepatotoxicity (DIH), also known as drug-induced liver injury (DILI), represents a pathological response to both synthetic and natural compounds, which can be acute or chronic (1). While its incidence is relatively low, DILI remains a major cause of acute liver failure in Europe, the United States, and Australia (2). The global annual incidence of DILI is estimated to range between 14 and 19.1 cases per 100,000 individuals exposed to potential hepatotoxic agents, with approximately 30% of affected patients developing jaundice (3). Key risk factors for DILI include female sex, advanced age, and an elevated body mass index (BMI) (4,5). More than 1,000 pharmaceutical drugs and herbal compounds are known to be hepatotoxic and are cataloged in the LiverTox database, a searchable resource (6). Other factors that may increase susceptibility to DILI include pre-existing liver disease, concomitant medication use, high dosages, the lipophilicity of the drug, and genetic predispositions (7).

DILI is typically classified into two mechanisms: predictable intrinsic (dose-dependent) and unpredictable (dose-independent). Unpredictable reactions, also known as immune-mediated hypersensitivity or non-immune reactions, occur in a smaller proportion of individuals (8). Intrinsic DILI is usually dose-dependent, affects a significant number of individuals, and has a short onset (hours to days) (9). Idiosyncratic DILI, on the other hand, is dose-independent but typically requires a threshold dose of 50-100 mg/day. It can be classified into hepatocellular, cholestatic, or mixed patterns and further divided into immune-mediated (allergic) or non-immune-mediated reactions. Immune-mediated cases are characterized by fever, rash, eosinophilia, and autoantibodies, whereas non-immune-mediated cases lack these features and have a delayed onset (10).

Approximately half of DILI cases are attributed to acetaminophen overdose. In addition to acetaminophen, DILI can be induced by various agents, with commonly reported ones being anti-tuberculosis agents such as isoniazid and rifampicin; antibiotics such as amoxicillin-clavulanate, tetracyclines, and macrolides; NSAIDs such as diclofenac; antifungal agents; antiepileptics; and halothane (8,11).

Liver injury is typically detected through biochemical tests such as alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and total bilirubin (TBL). In a 2011 expert working group, a new definition for drug-induced liver injury (DILI) was proposed, including ALT elevation ≥5 times the upper limit of normal (ULN), ALP elevation ≥2 times ULN (with an accompanying increase in gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT)), or ALT ≥3 times ULN with a simultaneous increase in total bilirubin concentration above 2 times ULN. Hepatocellular injury is classified when the ALT/ALP ratio is ≥5, cholestatic injury occurs with ALP ≥2 times ULN or an ALT/ALP ratio of ≤2, and mixed injury is identified when the ALT/ALP ratio is between 2 and 5.

Total bilirubin (TBL) is typically normal until the later stages of DILI, and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels are generally normal, although mild elevations (usually <2× ULN) may occur. Gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) levels can vary widely, with values ranging from low normal to >400 U/L. It is important to note that the majority of clinical trials utilize the ULN values from the central laboratory employed for the study, which can vary due to differences in reference populations and analytical variations in commercial assays (12,13)

A variety of scales have been developed to assess the causality of drug toxicity objectively (14). Among these, the CIOMS Roussel-Uclaf Causality Assessment Method (RUCAM) scale, the Maria & Victorino System, and the Clinical and Diagnostic Scale (CDS) are widely used, with RUCAM being the most commonly applied (15). Since drug-induced hepatotoxicity can present with symptoms similar to hepatobiliary disorders, it is crucial to conduct a comprehensive drug history when DILI is suspected. The diagnostic process begins by collecting detailed information, including the type of drug, dosage details (such as frequency, duration, and any adjustments), and the timing of symptom onset. A multidisciplinary approach involving the doctor, clinical pharmacist, and nurse is necessary for diagnosis, and regulatory agencies must be informed to evaluate the possibility of removing suspect drugs from the market (5). Clinical pharmacists play a pivotal role in the patient-centered diagnosis and treatment process, offering professional pharmaceutical expertise and comprehensive medication management. At our hospital, clinical pharmacists are integral in optimizing the DILI management model, providing timely and appropriate treatment recommendations for patients with DILI (16).

The aim of our study is to investigate the various causes of drug-induced liver injury, analyze the different patterns and outcomes of DILI in patients, and assess the role of the clinical pharmacist in managing this condition.

Methods

Study design

This retrospective, cross-sectional study was conducted between October 1, 2023, and October 1, 2024, on patients admitted to the third-level intensive care unit of a training and research hospital. The study focused on patients with elevated liver function and investigated DILI. The sample size of the study was determined based on the existing dataset without prior statistical power calculations. The number of patients included in the study was based on the available data.

Data collection

Data were collected from the hospital’s information management system. The study investigated the potential liver injury associated with the medications used in the treatment process of patients with elevated liver function. During data collection, liver function tests of patients were examined without specifically focusing on the presence of a clear drug relationship with DILI.

Inclusion criteria

Patients who fulfilled at least one of the clinical biochemical criteria for the diagnosis of drug- DILI were included in the study. These criteria include abnormal results in biochemical tests such as ALT, AST, ALP, and total bilirubin. Patients meeting these criteria were included to allow for the investigation of drug-induced liver injury.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with viral liver diseases, alcoholic liver disease, autoimmune liver disease, cholestatic liver diseases, infections (e.g., liver abscess), sepsis induced liver dysfunction, hepatobiliary pancreatic tumors, pancreatitis, direct liver injury, osteopathy, cirrhosis, and other drug-independent or unknown liver injuries were excluded from the study.

Diagnostic criteria

DILI is typically diagnosed and confirmed through abnormal results in biochemical tests such as ALT, AST, ALP, and total bilirubin. In 2011, an international expert working group proposed new criteria for the diagnosis of DILI. According to these criteria, an increase in ALT ≥5 times the upper limit of normal (ULN) or ALP ≥2 times the ULN, particularly in the presence of elevated gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT), and in the absence of known bone pathologies influencing ALP elevation, should raise suspicion for DILI. Additionally, a simultaneous elevation of ALT ≥3 times the ULN and total bilirubin concentration >2 times the ULN is considered a significant diagnostic criterion for DILI.

In our study, the type of liver injury is determined by the ALT/ALP ratio and ALT levels. When the ALT/ALP ratio is ≥5, the clinical condition is classified as hepatocellular. A rise in ALP of twofold or more, or an ALT/ALP ratio of ≤2, indicates a cholestatic condition. When the ALT/ALP ratio falls between 2 and 5, the clinical condition is considered mixed liver injury.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Marmara University Medical Faculty Research and Ethics Committee (09.2024.1229). The confidentiality of personal data was maintained, and all data were collected while ensuring patient anonymity. Informed consent was not obtained due to nature of the study.

Statistical analysis

The data collected in this study were analyzed using SPSS version 22.00. The Shapiro-Wilk test was employed to assess the normality of the distribution for numerical variables. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. Numerical variables with normal distribution were presented as mean ± standard deviation, whereas non-normally distributed variables were expressed as median and interquartile ranges (IQR). For comparisons of numerical variables, the Independent Samples t-test was used; if the assumptions of this test were not met, the Mann-Whitney U test was applied instead. The Chi-square test was used for comparisons of categorical variables; when the assumptions of the Chi-square test were not fulfilled, Fisher’s exact test was performed. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

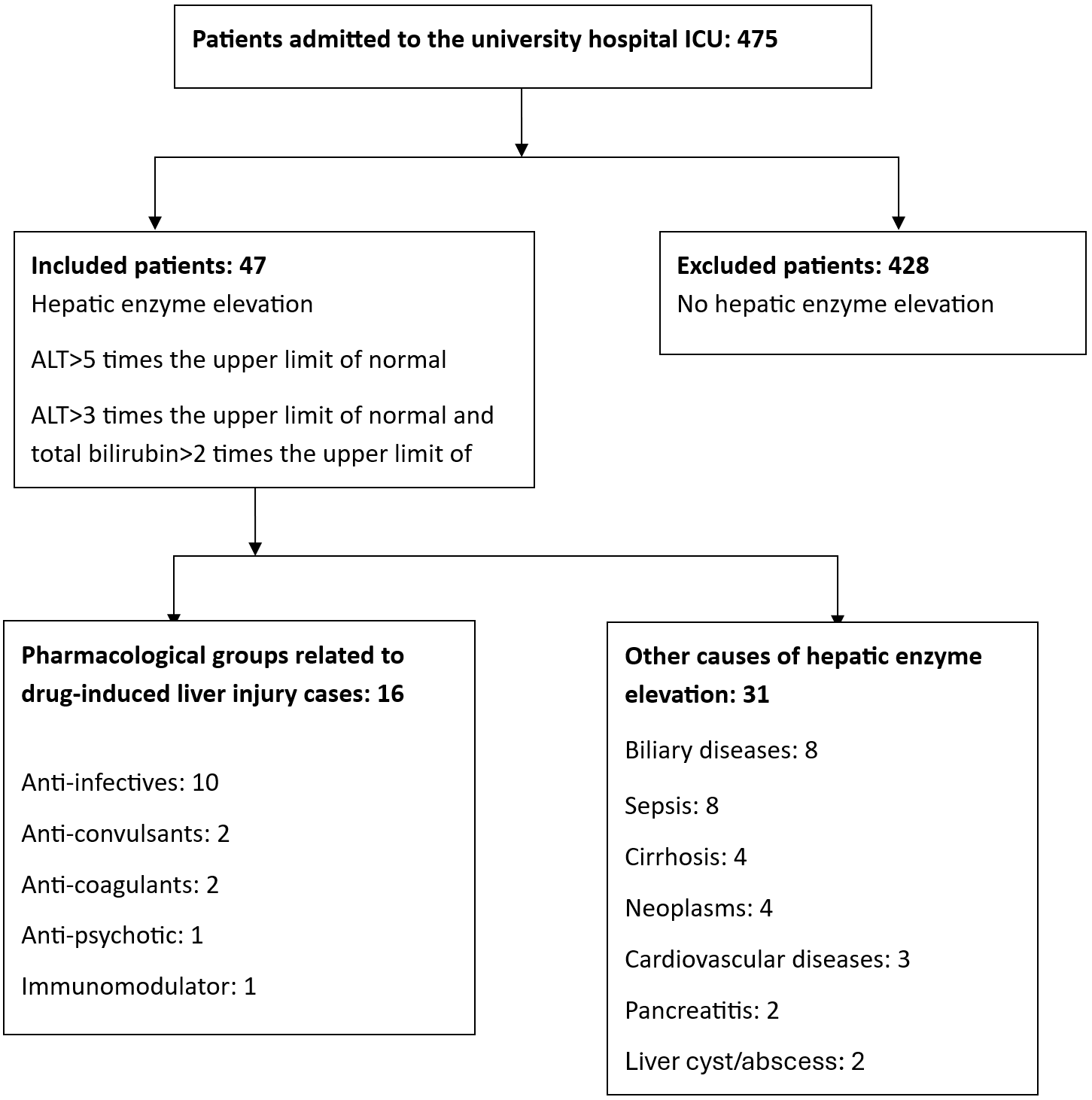

Among 475 patients admitted to the intensive care unit, altered liver test results were detected in 47 patients. Of these, 31 cases of hepatic enzyme elevation were attributed to non-drug-related causes, while 16 cases were identified as drug-induced liver injury (DILI) (Figure 1). The one-year incidence of DILI was calculated as 9.89%. The mean age of patients with DILI was 47.1±23.6 years; 7 patients (43.75%) were female and 9 (56.25%) were male (Table 1). The median Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score was 1 (1–3).

| CCI: Charlson Comorbidity Index. | ||||||||

| Table 1. Cases of drug-induced liver injury | ||||||||

| Patient number |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 11 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 12 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 13 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 14 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 15 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 16 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The most common ICU admission diagnoses among patients who developed DILI were intracranial hemorrhage or cerebral lesions (4 patients; 25%) and postoperative follow-up (4 patients; 25%). Additionally, 3 patients (18.8%) were admitted due to status epilepticus. The median APACHE II score was 18 (15–21) and the median SOFA score was 6 (4–8).

More than half of the patients with DILI (9 patients; 56.3%) were receiving eight different medications during treatment. The minimum number of medications administered was five. More than half of the patients (9; 56.3%) required vasopressor support. Table 2 shows each patient’s SOFA score on the day of peak liver enzyme elevation, vasopressor use, and average daily dose of paracetamol. Of the 16 DILI patients, 15 received paracetamol, with a mean daily dose of 1.16 g/day (range: 0–4 g/day).

| Table 2. DILI patients’ SOFA scores, vasopressor use, and paracetamol doses | |||

| Patient No |

|

|

(g/day) |

| 1 |

|

|

|

| 2 |

|

|

|

| 3 |

|

|

|

| 4 |

|

|

|

| 5 |

|

|

|

| 6 |

|

|

|

| 7 |

|

|

|

| 8 |

|

|

|

| 9 |

|

|

|

| 10 |

|

|

|

| 11 |

|

|

|

| 12 |

|

|

|

| 13 |

|

|

|

| 14 |

|

|

|

| 15 |

|

|

|

| 16 |

|

|

|

On ICU admission, the average ALT was 29±16 U/L, AST was 33±18 U/L, ALP was 77±26 U/L, and total bilirubin was 0.44±0.14 mg/dL. The average albumin level was 3.9±0.6 g/dL, INR was 1.09±0.15, and creatinine was 0.99±0.39 mg/dL. DILI developed approximately 9.5±5.2 days after ICU admission. After DILI onset, the average ALT was 375±152 U/L, AST was 283±157 U/L, and ALP was 141±88 U/L.

Among the drugs associated with DILI, antibiotics accounted for 62.5% (10 drugs). Other frequently associated drug classes included anticoagulants (2; 12.5%) and antipsychotics (2; 12.5%). The most commonly implicated agents were ampicillin-sulbactam (2; 12.5%), cefoperazone-sulbactam (2; 12.5%), enoxaparin (2; 12.5%), and quetiapine (2; 12.5%) (Table 3). The median duration of use for the suspected drugs was 8.5 days (5.25–14.75).

| Table 3. Values in liver tests | |||||||

| Suspected Drug |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cefoperazone-sulbactam |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cefoperazone-sulbactam |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Quetiapine |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Enoxaparin |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Enoxaparin |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ampicillin-sulbactam |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ampicillin-sulbactam |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Valproic acid |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ceftriaxone |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Clindamycin |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Imipenem |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| IVIG |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Daptomycin |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Quetiapine |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Tigecycline |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ceftazidim |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The median R ratio used to assess injury type was 11.25 (5.35–12.4). The injury pattern was hepatocellular in 13 patients (81.25%), cholestatic in 2 patients (12.5%), and mixed in 1 patient (6.25%). In our cohort, the hepatocellular pattern of injury together with the latency period (median 9.5±5.2 days after ICU admission) and RUCAM scores (≥6) strongly supported the diagnosis of drug-induced liver injury. Importantly, although nine patients were receiving vasopressors at the time of peak enzyme elevation, the biochemical profile was not consistent with ischemic hepatitis or sepsis-associated liver dysfunction. In particular, transaminase elevations did not exceed 1000 U/L, bilirubin levels remained largely within normal limits (0.3–0.9 mg/dL), and the pattern of injury was not compatible with sepsis-related cholestasis, where conjugated hyperbilirubinemia and cholestatic enzyme elevations usually predominate. These findings indicate that the observed liver injury was more plausibly attributable to DILI rather than sepsis or ischemia.

Among DILI cases, 7 patients (43.75%) showed clinical improvement and normalization of liver tests after liver-protective and supportive therapy. However, 9 patients (56.3%) died. Demographic characteristics such as age and gender were not associated with mortality. Likewise, ALT, AST, and ALP levels at both admission and during DILI episodes were not significantly associated with mortality (p>0.05).

Discussion

This study provides valuable insight into the incidence, clinical characteristics, implicated agents and outcomes of drug-induced liver injury (DILI) among critically ill patients in a tertiary intensive care unit (ICU) over the span of one year. Our findings indicate a DILI incidence of 9.89% among ICU patients presenting with elevated liver enzymes. In a recent study from a university hospital in Colombia, the 1-year incidence of drug-induced liver injury (DILI) was approximately 6%. Similar to our findings, antibiotics and anticonvulsants were reported as the main pharmacological groups associated with DILI. These results are in line with our observations, further supporting the notion that careful patient selection, close monitoring, and rational prescribing are essential in minimizing the risk of DILI. Consistent with the recommendations of this study, the prompt suspension of the suspected agent should be considered the first protective measure, followed, when appropriate, by modification of pharmacotherapy or the initiation of supportive treatment strategies (17).

In critically ill patients, liver enzyme elevations and drug-related hepatotoxicity are increasingly recognized as significant contributors to morbidity and mortality. A study reported that intensive care unit (ICU) patients with elevated liver enzymes at admission had significantly higher mortality compared to those with normal levels, emphasizing the prognostic relevance of hepatic dysfunction in critical illness (18). In our cohort, the liver enzyme abnormalities predominantly exhibited a hepatocellular pattern, with transaminase elevations exceeding cholestatic markers and bilirubin levels largely within normal limits. This biochemical profile contrasts with sepsis-associated cholestatic liver injury, which typically presents with conjugated bilirubin and ALP/GGT predominance and only mild transaminase elevation (8,19).

R values and RUCAM scores further support the attribution of these abnormalities to drug-induced liver injury (DILI) rather than sepsis or ischemic hepatopathy (6). Even among patients receiving vasopressors, the biochemical profiles remained inconsistent with sepsis-related liver dysfunction. These findings underscore that hepatocellular injury observed in the ICU can be differentiated from hemodynamic or infection-related liver damage.

Overall, this emphasizes the importance of vigilant monitoring, rigorous causality assessment, and early recognition of DILI in critically ill populations. These findings support the notion that both underlying critical illness and complex pharmacotherapy contribute to liver injury in ICU settings. In addition, findings highlight that critically ill patients are particularly susceptible to hepatotoxicity due to complex pharmacotherapy and polypharmacy, underscoring the need for vigilant monitoring, early detection, and rigorous causality assessment to mitigate potential adverse outcomes.

One of the factors potentially contributing to elevated liver enzyme levels is drug–drug interactions. The clinical relevance of these interactions in intensive care units has been emphasized in several studies (20). For example, some studies (21) have demonstrated that co-administration of interacting drugs can lead to increases in liver enzyme levels. In our study, however, no significant elevations in liver enzymes attributable to such interactions were observed. Nevertheless, this potential risk should be carefully considered in the management of intensive care patients.

A notable observation was the predominance of hepatocellular injury (81.25%) in our cohort, which is consistent with existing literature that identifies hepatocellular injury as the most common form of DILI (19,22). The onset of DILI approximately 9.5 days following ICU admission underscores the critical need for heightened vigilance during the second week of ICU stay, particularly when multiple high-risk medications are being administered.

In terms of causative agents, anti-infectives, particularly β-lactam antibiotics (e.g., ampicillin-sulbactam, cefoperazone-sulbactam, ceftriaxone), were the most commonly implicated drugs (19). This is unsurprising given the routine and extensive use of broad-spectrum antibiotics in ICU settings. Interestingly, the involvement of antipsychotics (such as quetiapine) and anticoagulants (like enoxaparin) as potential culprits despite being less frequently reported in the general population merits attention (23-25). Paracetamol use was common among patients with suspected DILI, but the daily doses were generally low and well below levels typically associated with hepatotoxicity in adults (26). These agents are more commonly used in ICUs, where off-label or extended-use practices are frequent. This emphasizes the need for ICU-specific DILI monitoring protocols, as opposed to relying solely on generalized hepatotoxicity data.

The mortality rate observed in our study (56.3%) was alarmingly high, significantly surpassing the mortality rates seen in non-ICU DILI cohorts. This increase likely reflects the severity of baseline illness among ICU patients, rather than DILI being the primary cause of death. However, it is important to acknowledge that DILI may exacerbate multi-organ dysfunction and increase susceptibility to sepsis, thereby indirectly worsening patient outcomes. Remarkably, neither demographic factors (age, gender) nor baseline liver enzyme levels were predictive of mortality, suggesting that DILI in the ICU is a multifactorial phenomenon intricately linked with the progression of critical illness (27,28).

An important strength of this study is the application of rigorous diagnostic criteria, including internationally recognized thresholds for DILI (ALT ≥5× ULN or ALT ≥3× ULN + total bilirubin >2× ULN), ensuring consistency and comparability with other studies. Furthermore, causality assessment was systematically performed using the RUCAM scale, which is considered the gold standard in hepatotoxicity causality assessment. Despite these strengths, the retrospective design introduces certain limitations, such as the potential underreporting of subtle DILI cases and the inability to account for confounding variables like parenteral nutrition, ischemic hepatitis, or undiagnosed infections (6,19,29).

From the clinical pharmacy perspective, this study underscores the pivotal role of clinical pharmacists in the early detection, risk stratification, and management of DILI in ICU. Routine medication profile reviews, proactive deprescribing strategies, and advocacy for liver-friendly therapeutic alternatives could significantly reduce the incidence of DILI in ICUs. In light of our findings, it is plausible to consider the implementation of prospective DILI screening protocols, led by clinical pharmacists with the collobration of intensivists, as a standard practice within ICU settings (16).

A critical revelation from our study is the often subtle, insidious onset of DILI in ICU patients. At ICU admission, liver function tests were predominantly normal or near-normal. Relying solely on initial admission laboratory results could create a false sense of security. Therefore, dynamic and repeated liver function tests should be an integral part of ongoing ICU pharmacovigilance (30,31).

Study strengths and limitations

This study’s strengths include its focus on a high-risk ICU patient population, the use of internationally validated diagnostic and causality tools, and its strong practical relevance to real-world clinical practice. However, the relatively small sample size and single-center design limit the generalizability of our findings. Additionally, the absence of liver biopsy data and the retrospective nature of the study preclude the definitive exclusion of all potential causes of liver injury.

Future research should focus on multicenter prospective studies to validate these findings and identify predictive biomarkers for early detection of DILI in ICU patients. Machine learning approaches that analyze large, multicenter datasets could provide insights into subtle risk patterns that may elude conventional analysis.

Conclusion

DILI remains an important, yet often underrecognized, complication in ICU patients. Anti-infectives, particularly β-lactam antibiotics, dominate the list of implicated drugs, with hepatocellular injury being the most common manifestation. Clinical vigilance, dynamic liver function monitoring, and the active involvement of clinical pharmacists are essential for mitigating DILI-related morbidity and mortality. Establishing structured DILI surveillance programs in ICUs is a forward-thinking strategy that can significantly enhance patient safety and improve clinical outcomes.

Highlights

- DILI incidence among ICU patients was 9.89% emphasizing that hepatotoxicity is a significant yet often overlooked complication in critically ill patients.

- Antibiotics were the most frequently implicated drug class (62.5%), particularly β-lactam antibiotics, highlighting the need for cautious use in ICU settings.

- Hepatocellular injury was the dominant pattern (81.25%), and DILI onset occurred approximately 9.5 days after ICU admission, underscoring the importance of dynamic liver monitoring beyond initial hospitalization.

- The mortality rate among DILI patients reached 56.3%, indicating the critical role of early detection and interdisciplinary management, particularly involving clinical pharmacists.

Ethical approval

This study has been approved by the Marmara University Medical Faculty Research and Ethics Committee (approval date: 18.10.2024, number: 09.2024.1229).

Source of funding

The authors declare the study received no funding.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Fisher K, Vuppalanchi R, Saxena R. Drug-Induced Liver Injury. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139:876-87. https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2014-0214-RA

- McGill MR, Jaeschke H. Biomarkers of drug-induced liver injury. Adv Pharmacol. 2019;85:221-39. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.apha.2019.02.001

- Garcia-Cortes M, Robles-Diaz M, Stephens C, Ortega-Alonso A, Lucena MI, Andrade RJ. Drug induced liver injury: an update. Arch Toxicol. 2020;94:3381-407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-020-02885-1

- Njoku DB. Drug-induced hepatotoxicity: metabolic, genetic and immunological basis. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:6990-7003. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms15046990

- Real M, Barnhill MS, Higley C, Rosenberg J, Lewis JH. Drug-Induced Liver Injury: Highlights of the Recent Literature. Drug Saf. 2019;42:365-87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-018-0743-2

- LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012.

- Germani G, Battistella S, Ulinici D, et al. Drug induced liver injury: from pathogenesis to liver transplantation. Minerva Gastroenterol (Torino). 2021;67:50-64. https://doi.org/10.23736/S2724-5985.20.02795-6

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Drug-induced liver injury. J Hepatol. 2019;70:1222-61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2019.02.014

- Bessone F, Hernandez N, Tagle M, et al. Drug-induced liver injury: A management position paper from the Latin American Association for Study of the liver. Ann Hepatol. 2021;24:100321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aohep.2021.100321

- Chitturi S, Farrell GC. Drug-Induced Liver Disease. In: Schiff’s Diseases of the Liver. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119950509.ch27

- David S, Hamilton JP. Drug-induced Liver Injury. US Gastroenterol Hepatol Rev. 2010;6:73-80.

- Aithal GP, Watkins PB, Andrade RJ, et al. Case definition and phenotype standardization in drug-induced liver injury. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89:806-15. https://doi.org/10.1038/clpt.2011.58

- Regev A, Palmer M, Avigan MI, et al. Consensus: guidelines: best practices for detection, assessment and management of suspected acute drug-induced liver injury during clinical trials in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49:702-13. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.15153

- Lucena MI, Camargo R, Andrade RJ, Perez-Sanchez CJ, Sanchez De La Cuesta F. Comparison of two clinical scales for causality assessment in hepatotoxicity. Hepatology. 2001;33:123-30. https://doi.org/10.1053/jhep.2001.20645

- Chalasani NP, Maddur H, Russo MW, Wong RJ, Reddy KR, Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Idiosyncratic Drug-Induced Liver Injury. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:878-98. https://doi.org/10.14309/ajg.0000000000001259

- Li D, Dong J, Xi X, et al. Impact of pharmacist active consultation on clinical outcomes and quality of medical care in drug-induced liver injury inpatients in general hospital wards: A retrospective cohort study. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:972800. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.972800

- Cano-Paniagua A, Amariles P, Angulo N, Restrepo-Garay M. Epidemiology of drug-induced liver injury in a University Hospital from Colombia: Updated RUCAM being used for prospective causality assessment. Ann Hepatol. 2019;18:501-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aohep.2018.11.008

- Yiğit E, Çetin T, Taşkıran G, et al. Elevation of liver enzymes in intensive care patients is significantly related with the increased mortality. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2019;30(Suppl 1):S94. https://doi.org/10.5152/tjg.2019.62

- Björnsson ES. The epidemiology of newly recognized causes of drug-induced liver injury: an update. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2024;17:520. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph17040520

- Gülen D, Dağdelen MŞ, Ceylan İ, Kelebek Girgin N. Potential drug-drug interactions in intensive care units in Turkey: a point prevalence study. Turk J Intensive Care. 2023;21(2):93-9. https://doi.org/10.4274/tybd.galenos.2022.32932

- Ho YF, Chou HY, Chu JS, Lee PI. Comedication with interacting drugs predisposes amiodarone users in cardiac and surgical intensive care units to acute liver injury: a retrospective analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e12301. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000012301

- Jiang F, Yan H, Liang L, et al. Incidence and risk factors of anti-tuberculosis drug induced liver injury (DILI): Large cohort study involving 4652 Chinese adult tuberculosis patients. Liver Int. 2021;41:1565-75. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.14896

- Roger C, Louart B. Beta-Lactams Toxicity in the Intensive Care Unit: An Underestimated Collateral Damage? Microorganisms. 2021;9:1505. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9071505

- He S, Chen B, Li C. Drug-induced liver injury associated with atypical generation antipsychotics from the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS). BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2024;25:59. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40360-024-00782-2

- Eze IE, Adidam S, Gordon DK, Lasisi OG, Gajjala J. Probable enoxaparin-induced liver injury in a young patient: a case report of a diagnostic challenge. Cureus. 2023;15:e36869. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.36869

- Watkins PB, Kaplowitz N, Slattery JT, et al. Aminotransferase elevations in healthy adults receiving 4 grams of acetaminophen daily: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296:87-93. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.296.1.87

- Abid A, Subhani F, Kayani F, Awan S, Abid S. Drug induced liver injury is associated with high mortality-A study from a tertiary care hospital in Pakistan. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0231398. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231398

- Sunil Kumar N, Remalayam B, Thomas V, Ramachandran TM, Sunil Kumar K. Outcomes and Predictors of Mortality in Patients With Drug-Induced Liver Injury at a Tertiary Hospital in South India: A Single-Centre Experience. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2021;11:163-70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jceh.2020.08.008

- Tajiri K, Shimizu Y. Practical guidelines for diagnosis and early management of drug-induced liver injury. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:6774-85. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.6774

- Tiwari V, Shandily S, Albert J, et al. Insights into medication-induced liver injury: Understanding and management strategies. Toxicol Rep. 2025;14:101976. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxrep.2025.101976

- Sehrawat SS, Premkumar M. Critical care management of acute liver failure. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2024;43:361-76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12664-024-01556-8

Copyright and license

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is properly cited.