Abstract

Objective: The aims of the study was to identify and visualize studies conducted between 2006 and 2025 in the fields of sepsis and artificial intelligence in intensive care units, with the aim of revealing trends in this area.

Materials and Methods: The data were obtained from the Web of Science Core Collection database on May 2, 2025. Performance analysis, visualization, mapping, and bibliometric analyses were performed using the R software program Biblioshiny interface. For bibliometric data, a search was conducted in the WoS database using the keywords “intensive care” OR “ICU” OR “intensive care unit” OR “ICUs” AND “artificial intelligence” OR “machine learning” OR “deep learning” AND ‘Sepsis’ OR “sepsis prediction” in all files. The analysis of the study was conducted using 1,072 publication data.

Results: The study found that the average annual number of articles produced in intensive care units in the fields of sepsis and artificial intelligence obtained from the WoS database was 2.76, with an annual growth rate of 27.63. A total of 1,072 articles were produced in 371 journals between 2006 and 2025. A total of 1,531 keywords were used. The average number of citations per publication was 18.13. It was observed that authors used 2,255 keywords across all publications, 7,015 authors were involved in these publications, only 6 articles had a single author, the average number of co-authors per article was 8.95, and the international co-authorship rate was 21.64%.

Conclusions: The results of the bibliometric analysis showed that studies in this field are extremely recent. Studies conducted between 2006 and 2025 on sepsis and artificial intelligence in intensive care units have been included in the literature.

Keywords: Artificial intelligence, bibliometric, Bibliyoshiny, intensive care unit, machine learning, sepsis

Introduction

Sepsis is a life-threatening condition resulting from a dysregulated host response to infection and remains one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide (1-5). In intensive care units (ICUs), where the most critically ill patients are treated, early diagnosis and prompt intervention are crucial to reducing mortality (6). Although clinical tools such as the Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS), Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS), and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) are used to aid in sepsis diagnosis, early detection remains a major challenge due to the syndrome’s heterogeneous nature and variable presentation (7,8).

The widespread adoption of electronic health records (EHRs) has resulted in the accumulation of large volumes of patient information; however, the heterogeneous and unstructured nature of these data presents significant analytical challenges. In this context, artificial intelligence (AI), particularly machine learning (ML) techniques, has emerged as a promising approach for handling complex clinical data and facilitating earlier identification of sepsis (9- 11). Previous studies indicate that these AI-driven approaches contribute to improved clinical outcomes, such as decreased mortality rates and reduced lengths of stay in intensive care units, by supporting timely clinical interventions (12,13).

Although several systematic reviews and retrospective analyses have explored the application of artificial intelligence in sepsis prediction (14,15), no bibliometric investigation has been conducted to comprehensively evaluate global research patterns, collaborative networks, and the evolution of key themes in this domain. This lack of bibliometric evidence underscores the necessity of a detailed mapping of the existing literature to inform and guide the future development of AI-supported sepsis management strategies in intensive care settings.

The present study seeks to map and critically assess worldwide scientific trends in research on artificial intelligence applications for sepsis in intensive care units by employing bibliometric techniques through the Biblioshiny platform. By identifying the most influential publications, authors, and collaboration networks, this study intends to provide guidance for future interdisciplinary research and emphasize the value of integrating AI into critical care practices.

Research questions

- What is the publication trend by year?

- What is the annual number of citations?

- What is the co-occurrence map of author keywords?

- What are the nodes and clusters formed by keywords?

- Who are the most productive authors?

- What are the most influential journals?

- Which country is the most influential for publications?

- What are the thematic maps like?

- What is the thematic evolution like?

Methods

Study design

In this study, a descriptive and evaluative bibliometric analysis of articles published on sepsis and AI in ICU was performed. The bibliometric analysis method provides researchers with a broader literature profile through performance analysis, visualization and relationship analysis (16). Therefore, bibliometric analysis was used in this study for a deeper research and to reveal the relationship of social networks with the tracking of trends.

Data collection

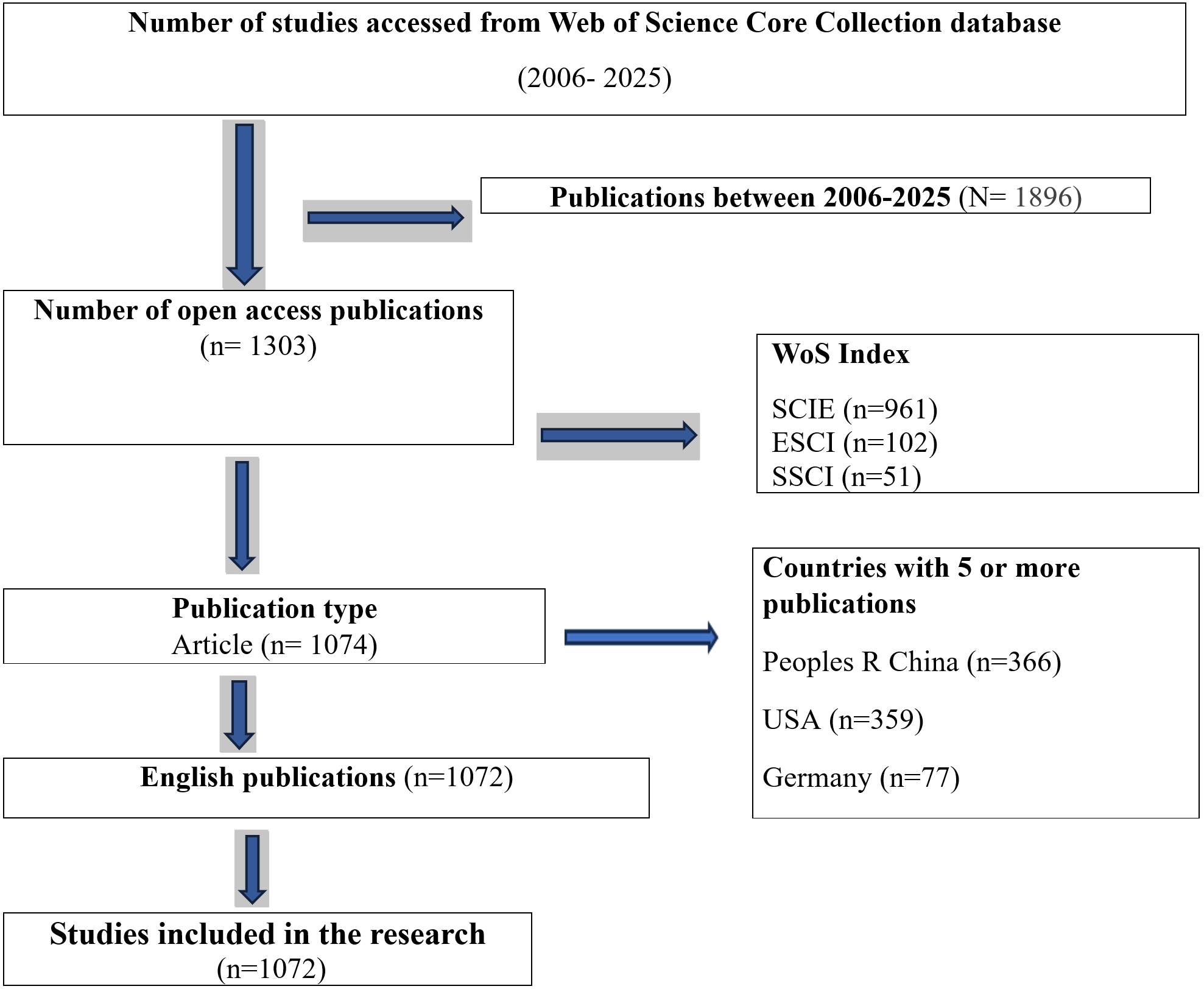

This study consists of a dataset of 1,072 open access articles obtained from the WoS database. In this study, research published in the Web of Science Core Collection (WoSCC) database on sepsis and artificial intelligence in intensive care units was examined from a bibliometric perspective with the aim of revealing the current situation at the international level. An important point in bibliometric analyses is the databases from which the data set will be obtained. Currently, there are multiple databases available for bibliometric analyses. Among the most frequently used databases are PubMed, Embase, Scopus, SpringerLink, Google Scholar, and ScienceDirect. These databases possess distinct characteristics (17). Compared to Scopus and Google Scholar, the WoS database is a more reliable database due to its broader journal and citation archive, which dates back to earlier years, its inclusion of journals with higher impact values, its effective access to bibliographic data, and its larger number of publications. Therefore, as in many bibliometric studies, it has been the preferred database for obtaining data in this study (18-22). The data for the study were obtained from the “Web of Science (WoS) Core Collection” database on May 2, 2025, from among the open access publications found between 2006 and 2025. For bibliometric data, an advanced search was performed in all files in the WoS database ((((((( ((ALL=(“intensive care”)) OR ALL=(“ICU”)) OR ALL=(“intensive care unit”)) OR ALL=(‘ICUs’)) AND ALL=(“artificial intelligence ”)) OR ALL=(“Machine Learning” )) OR ALL=(“deep learning”)) AND ALL=(“Sepsis” )) OR ALL=(“Sepsis Prediction” )) and Open Access and Article (Document Types) and Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI-EXPANDED) or Emerging Sources Citation Index (ESCI) or Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) and English (Languages) The research universe was found to be 1896. When the publication language, year, countries, institutions, authors, and publication type were searched in the Science Citation Index Expanded, Social Sciences Citation Index, Emerging Sources Citation Index, and the publication year was limited to 2006-2025, the sample was found to be 1072. The analysis of the study was performed on 1072 publication data. The studies comprising the research dataset were selected from the WoS database according to publication acceptance criteria and are presented in the publication flow diagram (Figure 1).

Data analysis

All information related to publications has been filtered according to research acceptance criteria. After filtering, the record contents of 1,072 publications obtained from the WoS database were selected as full records and references. Publications between 1 and 500 were exported as file 1, those between 501 and 1,000 as file 2, and those between 1,001 and 1,072 as file 3 in BibTEX format. The files containing the exported data were combined into a single file in the BibTEX file for analysis and organized in the R software program interface to be suitable for analysis. The Biblioshiny program, which is preferred for bibliometric analysis, was loaded into the R software program interface as the analysis tool. Biblioshiny facilitates the visual representation of interconnections among scientific publications, allowing documents to be organized according to shared thematic characteristics (23). By offering a user-friendly interface, Biblioshiny streamlines the otherwise complex process of thematic analysis, rendering it more accessible, interpretable, and efficient. Identifying thematic patterns and emerging trends within the scientific literature is essential for supporting researchers and policymakers in recognizing both current priorities and prospective research trajectories (24).

Within the framework of general structure analysis, Biblioshiny provides comprehensive information on datasets, journals, and authors, alongside descriptive bibliometric indicators and analyses of intellectual structure. These evaluative bibliometric analyses encompass conceptual, social, and intellectual dimensions of the literature. In network visualizations, nodes denote the core analytical units, such as keywords, authors, or research topics (25). For instance, keyword-based analyses enable the examination of popularity trends within specific research domains. Connections between nodes, represented as links, reflect the relationships and associations among these elements, with the existence of a link indicating a meaningful connection (26).

Clustering techniques group nodes with similar or related characteristics, thereby highlighting collections of elements that converge around particular themes or subject areas (27). Furthermore, node attributes such as size or color are used to represent quantitative or qualitative metrics; for example, the frequency of a keyword within the literature can be inferred from node size (28). Finally, the overall topology of the bibliometric map illustrates the structural relationships among themes, providing insight into how different research areas are interconnected.

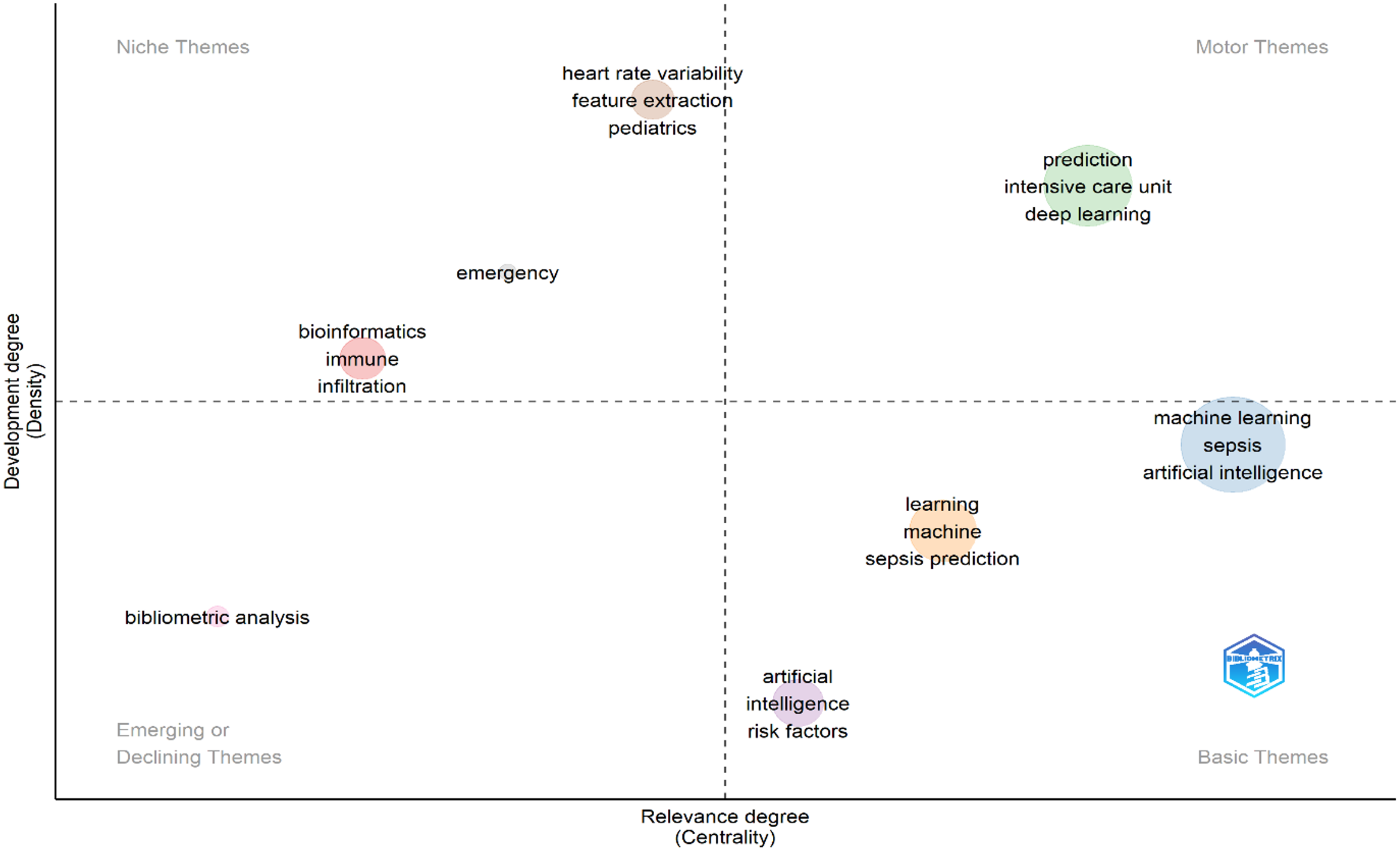

Clusters connected by dense links may indicate a strong relationship (23). Obvious gaps or anomalies in the map may indicate areas that have not been sufficiently researched in the literature or unexpected relationships (28). In this study, thematic maps, trend topics, and thematic evolution analyses were used to focus on thematic trends and the evolution of studies. The four quadrants in the thematic map are defined as follows:

1. Motor themes: The clusters in the upper right quadrant are highly developed and important themes. This quadrant consists of strong themes. The centrality and density of the clusters are high.

2. Niche themes: The upper left quadrant consists of clusters with low centrality and high density. These clusters have few but strong connections with other themes.

3. Basic themes: The clusters in the lower right are themes that have many connections with other themes but weak relationships.

4. Emerging or declining themes: Clusters in the lower left quadrant represent themes with few and weak connections to other themes (29,30).

Results

Characteristics of publications

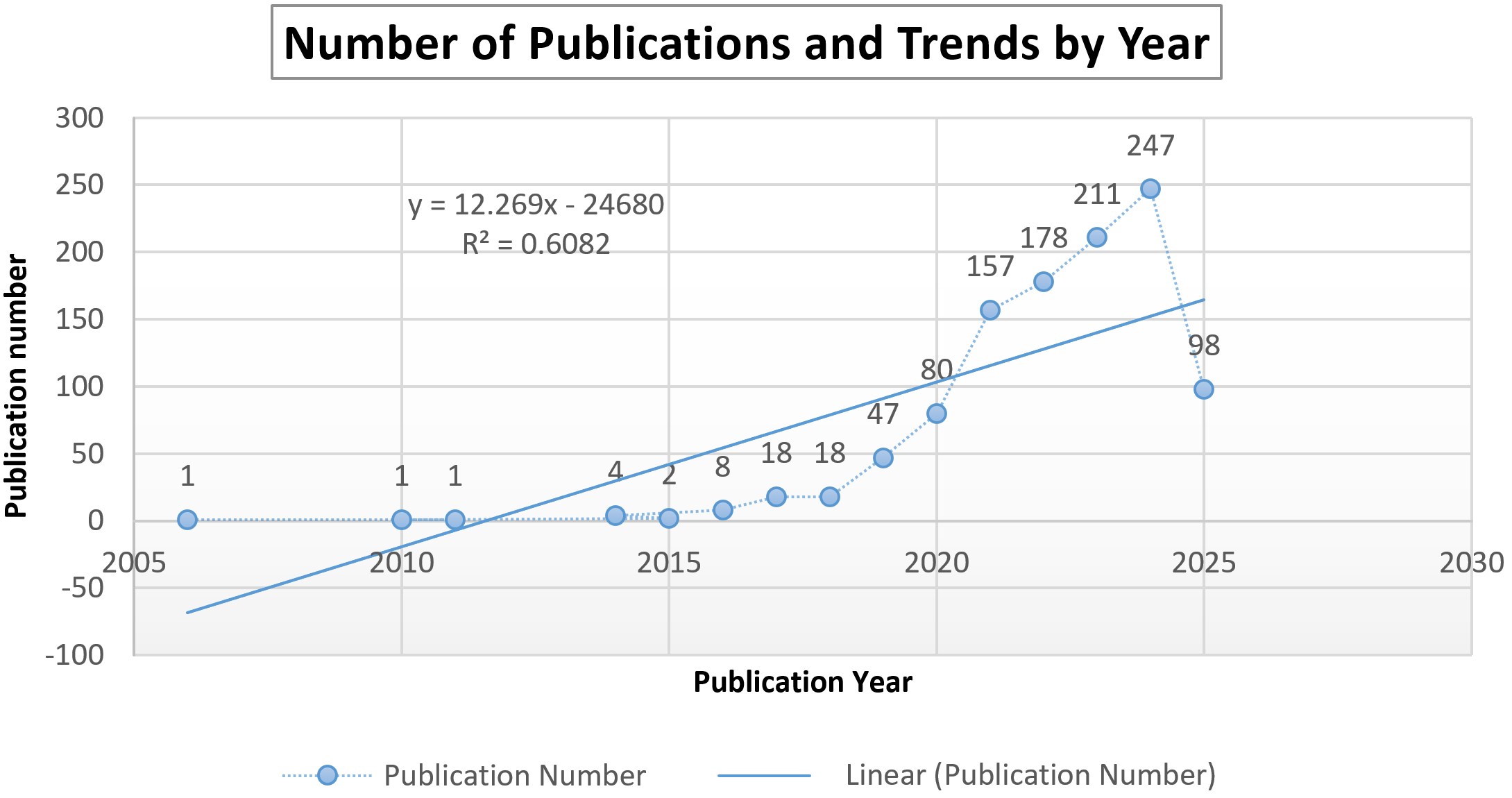

When examining the distribution of publications by year, it was observed that the first publication within the data set was made in 2006 (n=1) and contributed 0.093 to the current publications, that there has been an upward trend in the number of publications since 2019, and that there has been significant growth in the number of publications between 2021 and 2022. In 2024, the highest number of publications was recorded (n=247), accounting for 23.041% of the total (Table 1).

| Table 1. Distribution of publications by years (2006-2025) | ||

| Publication Years |

|

|

| 2024 |

|

|

| 2023 |

|

|

| 2022 |

|

|

| 2021 |

|

|

| 2025 |

|

|

| 2020 |

|

|

| 2019 |

|

|

| 2017 |

|

|

| 2018 |

|

|

| 2016 |

|

|

| 2014 |

|

|

| 2015 |

|

|

| 2006 |

|

|

As a result of bibliometric analysis, it was found that there were 1,072 articles published, with an average of 2.76 articles produced annually in the field of sepsis and artificial intelligence, and an annual growth rate of 27.63. Between 2006 and 2025, 1,072 articles were produced in 371 journals. A total of 1,531 keywords were used. The average number of citations per publication was 18.13. It was observed that authors used 2,255 keywords for all publications, 7,015 authors were involved in these publications, there were only 6 single-authored articles, the average number of co-authors per article was 8.95, and the international co-authorship rate was 21.64% (Table 2).

| Table 2. Basic information on bibliometric analysis | |

| Description |

|

| Main Information About Data |

|

| Timespan |

|

| Sources (Journals) |

|

| Documents |

|

| Annual Growth Rate % |

|

| Document Average Age |

|

| Average citations per doc |

|

| References |

|

| Document Contents |

|

| Keywords Plus (ID) |

|

| Author's Keywords (DE) |

|

| Authors |

|

| Authors |

|

| Authors of single-authored docs |

|

| Authors Collaboration |

|

| Single-authored docs |

|

| Co-Authors per Doc |

|

| International co-authorships % |

|

| Document Types |

|

| Article |

|

Regression analysis results regarding the accuracy of trends in publication growth

Linear regression analysis was performed to evaluate the change in the number of publications over the years. As a result of the analysis, it was found that there was a statistically significant increase in the number of publications over the years (Trend coefficient = 12.27; R² = 0.6082; p = 0.0006). These findings reveal that the increase in publications is not random and shows a consistent development in time. In addition, the explanatory power of the model is moderately strong, which supports the relationship between the regression line and the number of publications. The addition of these statistical tests increased the rigor of our analysis. “As a result of the linear regression analysis, it was determined that the number of publications increased significantly over the years (β = 12.27, p = .0006, R² = .608). This situation reveals that the productivity in the literature increased by an average of 12.27 publications per year during the period covered by the study. The 95% confidence interval of the trend coefficient is [6.92, 17.62], which indicates a steady growth in academic production.” (Graphic 1).

Interpretation of Publication Trend Coefficient

1. Trend Coefficient (β₁ = 12.27 publications/year): This coefficient shows that there has been an average increase of 12.27 publications per year throughout the years examined. This indicates that academic interest in the relevant scientific field has been increasing and productivity has been steadily increasing.

2. R² (0.608): The explanatory power of the model, R², is 60.8%. This means that approximately 61% of the changes in the number of publications are explained by the time (year) variable. In other words, the model shows a medium-high level of fit with the data.

3. p-value (0.0006): The trend coefficient obtained is statistically significant (p < 0.05). This shows that the increase in the number of publications over the years is not random, but rather a consistent and significant upward trend over time.

4. 95% Confidence Interval ([6.92, 17.62]): This interval shows that the annual publication increase is between 6.92 and 17.62 with a 95% probability. This proves that the increase is not only significant in the average but also in a safe interval (Graphic 1).

Trend topics and most influential journals

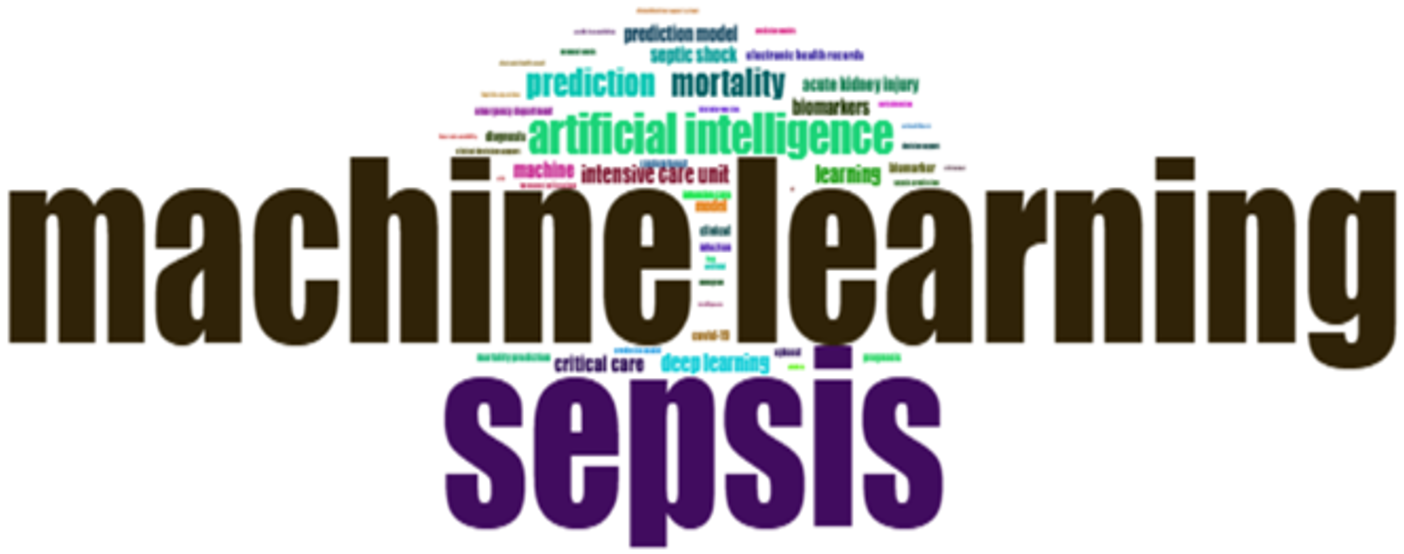

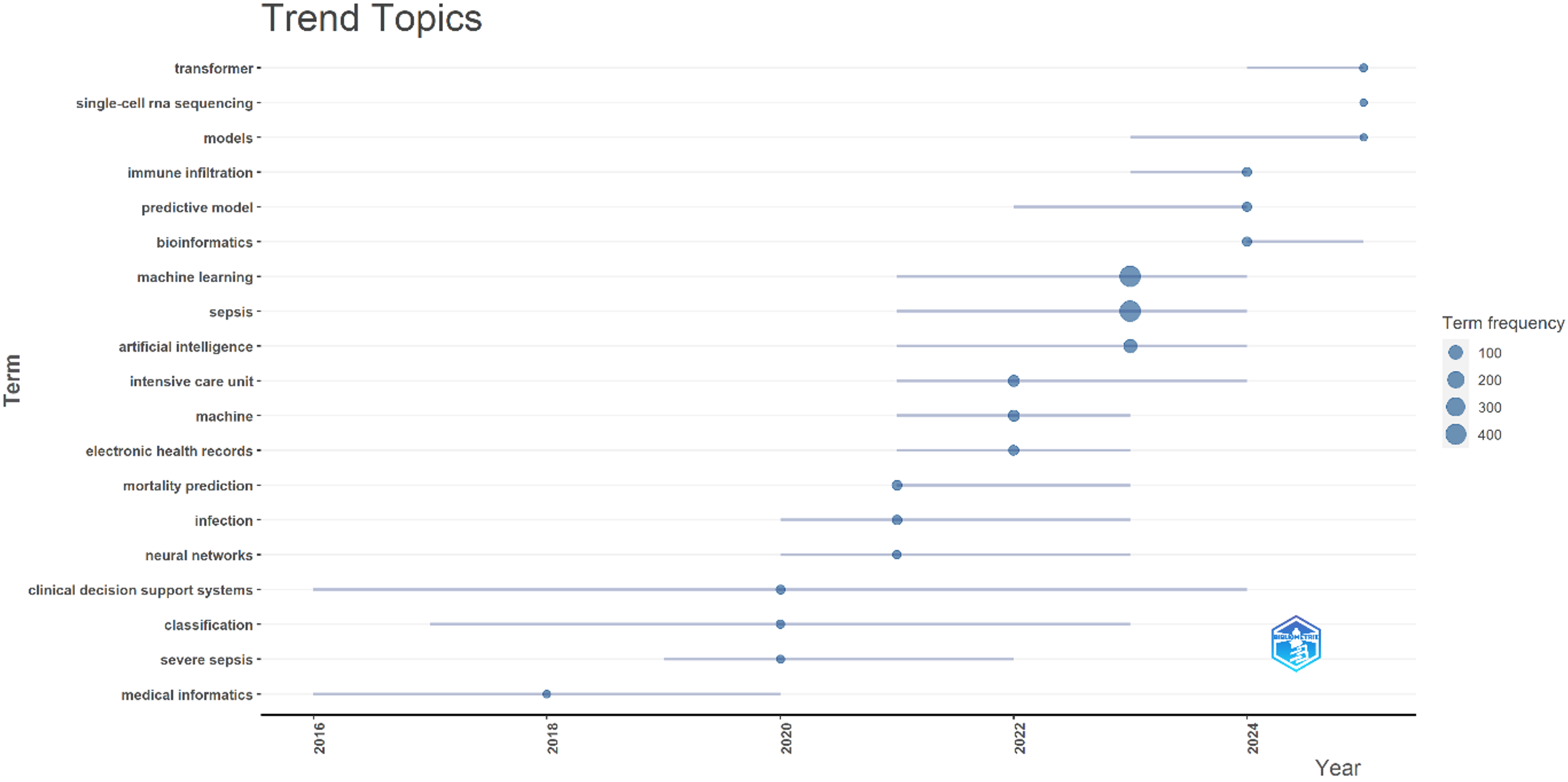

It has been reported that 1414 keywords were used as author keywords in studies conducted in intensive care units in the field of sepsis and artificial intelligence. The most frequently used author keyword cloud in studies conducted in intensive care units in the field of sepsis and artificial intelligence is shown in Figure 2. As the frequency of words increases, the keywords appear larger in the word distribution. Accordingly, the most frequently used author keywords are machine learning (429 times), sepsis (414 times), artificial intelligence (93 times), prediction (67 times), mortality (67 times), deep learning (42 times), critical care (40 times), intensive care unit (43 times), machine (38 times), learning (42 times), and septic shock (28 times) (Figure 2).

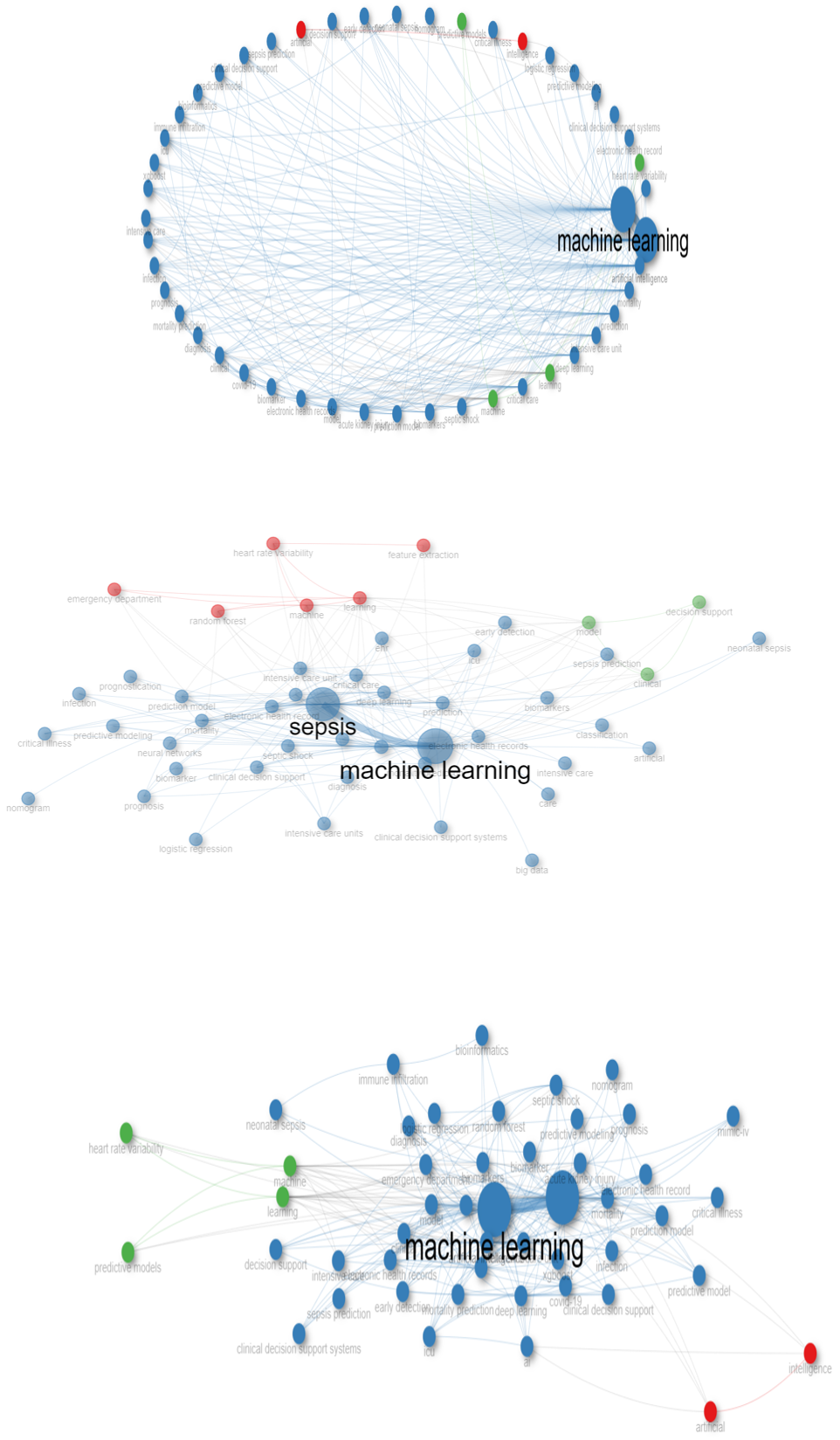

Figure 3 shows the co-occurrence map of author keywords. When creating this map, the number of nodes was set to 50 and the word co-occurrence ratio was set to 2. The higher the word co-occurrence ratio, the larger the nodes and words. The color of the nodes indicates the word co-occurrence. Sepsis and machine learning were the most frequently co-occurring words. The co-occurrence network of studies conducted in intensive care units in the fields of sepsis and artificial intelligence can be categorized into three clusters. The first cluster (red) contains the words Artificial (Betw = 0.15) and intelligence (Betw = 0). The second cluster (blue) includes machine learning (Betw = 408.98), sepsis (Betw = 409.43), artificial intelligence (Betw = 20.52), prediction (Betw = 5.04), mortality (Betw = 5.88), deep learning (Betw = 1.91), critical care (Betw =1.27), intensive care unit (Betw =1.10), septic shock (Betw =0.49), prediction model (Betw =0.45), acute kidney injury (Betw =0.67), biomarkers (Betw =3.87), electronic health records (Betw =1.15), COVID-19 (Betw =0.20), mortality prediction (Betw =0.16), biomarker (Betw =3.87), mortality prediction (Betw =0.16), clinical decision support (Betw =0.03), infection (Betw =0.06), prognosis (Betw =0.04), diagnosis (Betw =0.13), intensive care (Betw =0.003), predictive modeling (Betw =0), electronic health record (Betw =1.15), ICU (Betw =0.17), sepsis prediction (Betw =0), early detection (Betw =0), neonatal sepsis (Betw =0), prognostication (Betw =0), artificial (Betw = 0), big data (Betw = 0), care (Betw = 0), clinical decision support systems (Betw = 0), critical illness (Betw = 0), EHR (Betw = 0), intensive care units (Betw = 0.04), logistic regression (Betw = 0), AI (Betw = 0.19). The third cluster (green) consists of the words learning (Betw = 3.42), machine (Betw = 3.28), predictive models (Betw = 0.005), and heart rate variability (Betw = 0.004). The keywords in the second cluster are more suitable for researchers conducting studies in the field of intensive care sepsis artificial intelligence (Figure 3). The analysis revealed that “machine learning” was mentioned 428 times and “sepsis” 414 times among the most frequently studied trending topics between 2021, 2023, and 2024 (Figure 4).

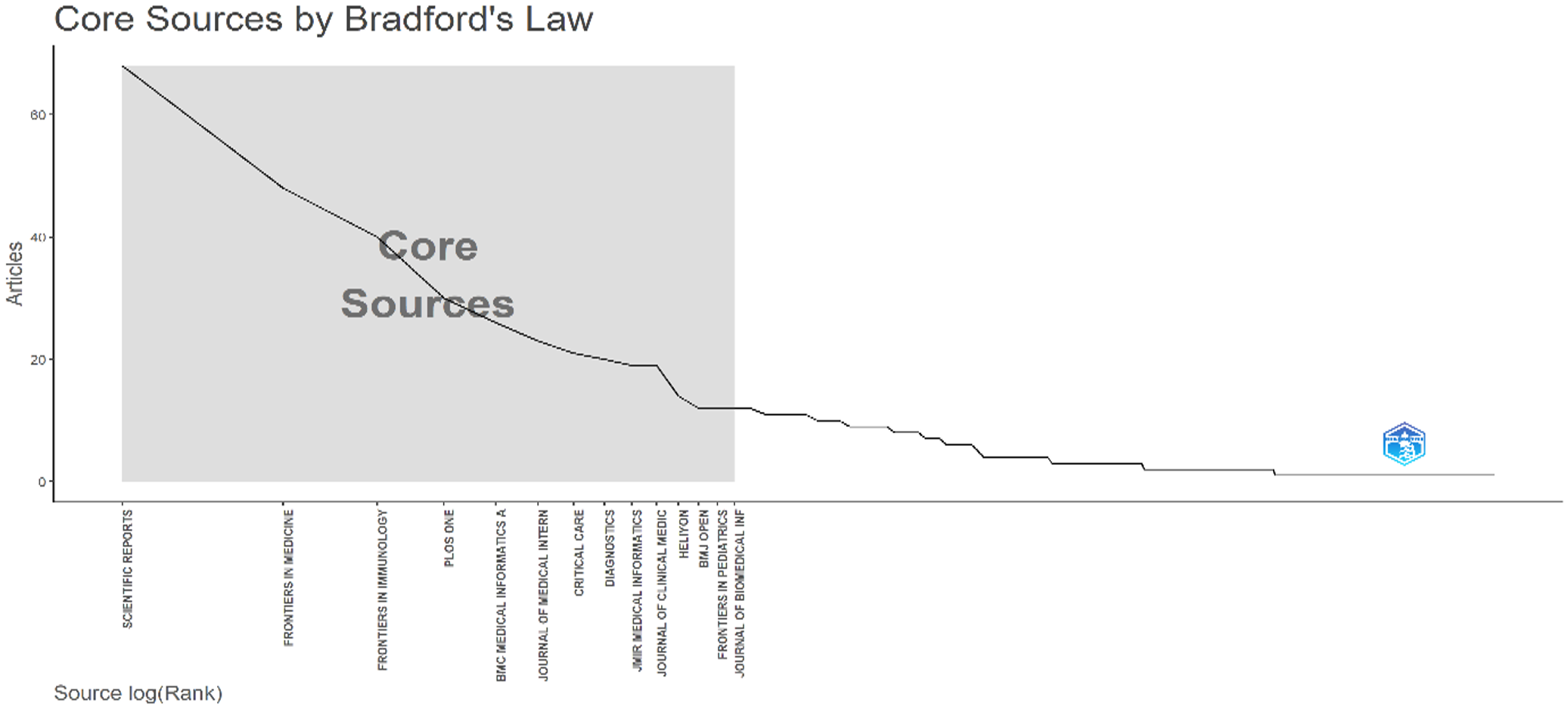

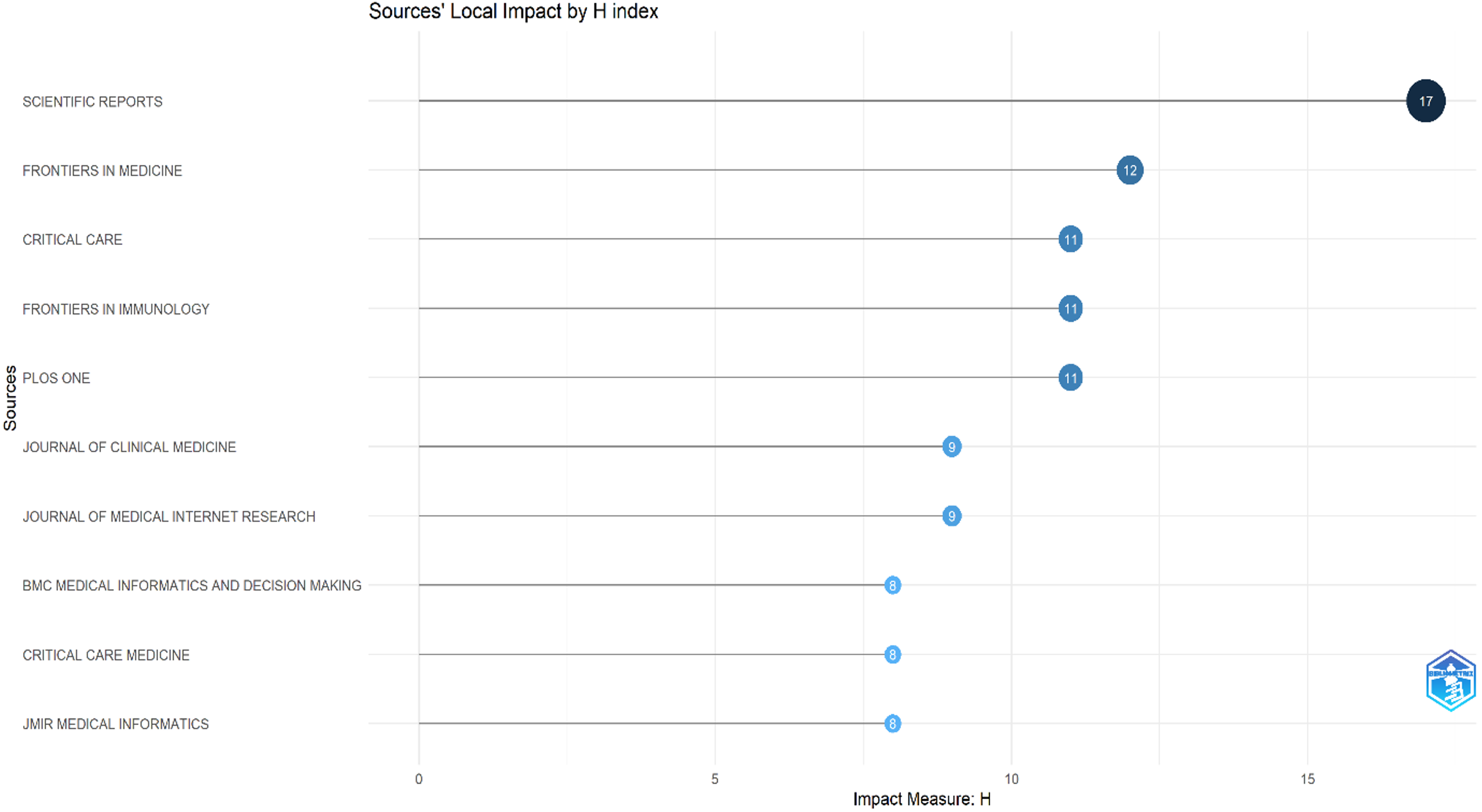

Kamaleswaran R (17 publications), Nemati S (16 publications), Das R (16 publications), and Wang Y (15 publications) were found to be the most prolific authors. Most of the studies were produced in Peoples R China (n=366), USA (n=359), and Germany (n=77). Most of the studies were published in Scientific Reports (68 publications; H index 17), Frontiers in Medicine (48 publications; H index 12), Frontiers in Immunology (40 publications; H-index 11), Critical Care (21 publications; H-index 11), and PLOS ONE (30 publications; H-index 11) (Figure 5 and Figure 6).

It is a model defined by Samuel C. Bradford in 1934 that predicts the exponentially decreasing returns of searching for references in scientific journals. According to Bradford’s Law, core journals containing the largest number of publications on a given topic are followed by second and third groups of journals containing fewer and fewer related publications, respectively. This law indicates that scientific knowledge is concentrated in a limited number of journals. Articles published on a scientific topic are distributed in journals containing progressively fewer articles, starting with core journals. This distribution follows a specific logarithmic pattern (31,32).

Tematic map

The theme typology of research in intensive care units in the field of sepsis and artificial intelligence is shown in Figure 7. In the thematic map analysis, the number of words is 100, the minimum cluster frequency is 3, and the number of levels per cluster is 3 (Figure 7). The motor themes in the upper right quadrant are characterized by both higher density and higher centrality and consist of words such as prevention intensive care unit and deep learning. The upper left quadrant, on the other hand, has lower centrality and higher density, contains niche themes, and shows insignificant external connections of limited importance, such as bioinformatics, immune, infiltration, heart rate variability, feature extraction pediatrics, and emergency. The lower right quadrant shows basic themes with lower density but higher centrality and includes words such as machine learning, sepsis, artificial intelligence, and sepsis prediction. The lower left quadrant shows themes with lower centrality and lower density. In particular, it includes words related to sepsis and artificial intelligence in intensive care units, which have low centrality and low density.

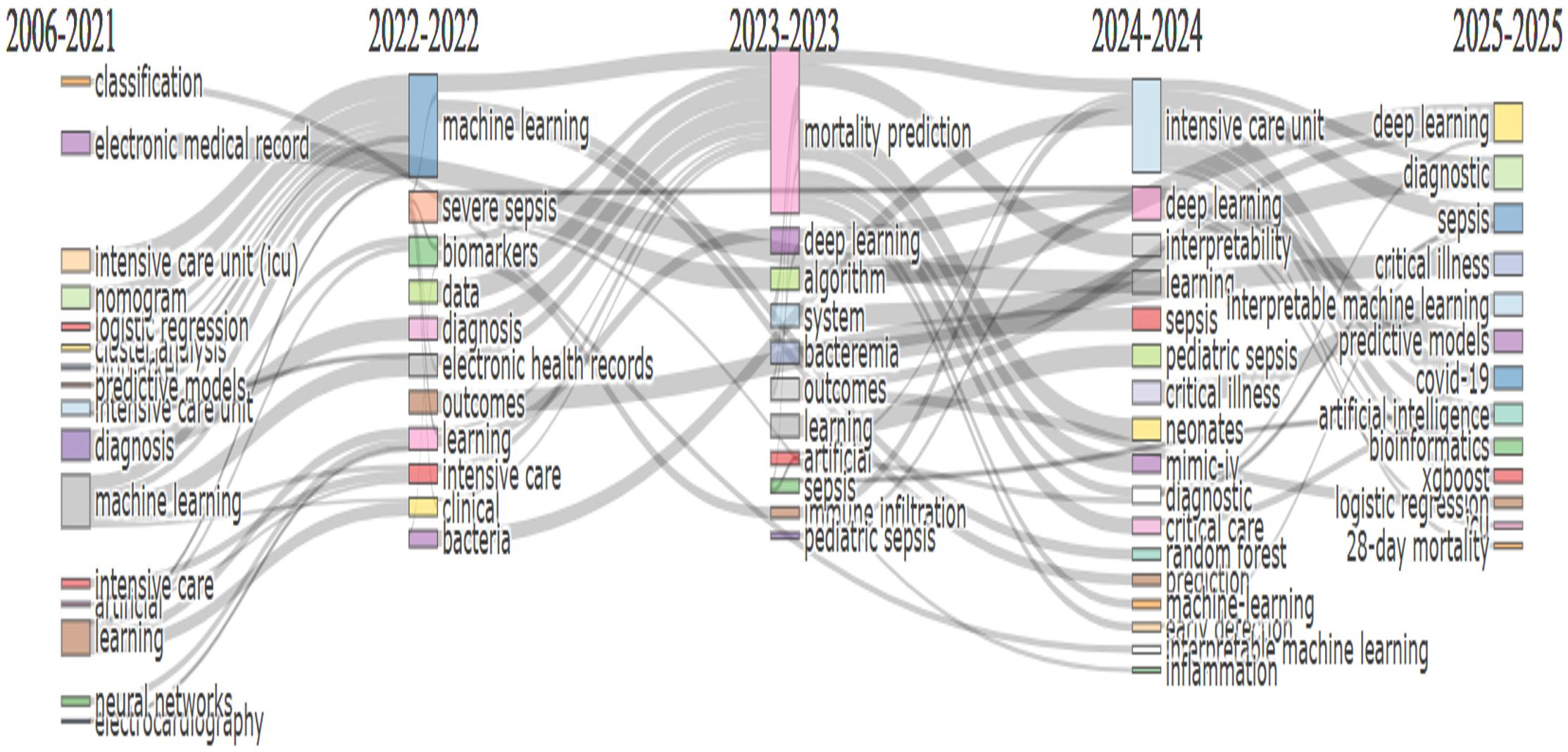

Figure 8 shows the thematic evolution of author keywords in four stages. Thematic evolution analysis enables the discovery of evolutionary correlations and trends in thematic contexts and evolutionary trends in structures (18). Figure 8 shows the correlation between different themes and their progress over a period of approximately 19 years: 2006-2021; 2022-2022; 2023-2023; 2024-2024 and 2025; 2025, divided into five stages. Between 2006 and 2021, the most frequently used keywords in the early years were electronic records, intensive care unit, intensive care, diagnosis, and machine learning, while in 2022, the keywords were machine learning, diagnosis, electronic records, intensive care, and bacteria. In 2023, the keywords that stood out were mortality rate prediction, deep learning, system, and bacteremia. In 2024, studies using author keywords such as intensive care unit, pediatric sepsis, sepsis, and deep learning are prominent. In 2025, the keywords deep learning, diagnosis, sepsis, artificial intelligence, and neonatal deaths are prominent (Figure 8).

Discussion

This bibliometric review, encompassing 599 publications published between 2006 and 2025, offers an in-depth depiction of the progression and transformation of artificial intelligence (AI) research related to sepsis within intensive care unit (ICU) settings. A substantial growth in the number of publications has been evident from 2019 onward, reaching its highest point in 2022. This escalation is likely associated with the expanding adoption of digital health technologies and the heightened emphasis on early sepsis identification during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In contrast to conventional bibliometric analyses focusing on sepsis research (32,33), the present study identifies a distinct evolution in thematic priorities. Earlier investigations predominantly highlighted terms such as “ICU” and “septic shock,” whereas more recent literature increasingly concentrates on concepts including “machine learning,” “predictive modeling,” and “deep learning.” This transition underscores the growing reliance on data-driven methodologies for early sepsis recognition, which may address the inherent limitations of traditional clinical scoring systems, such as SIRS and SOFA (34-36). The rising prominence of predictive modeling further suggests a research response to clinical demands for earlier and more personalized interventions among critically ill patients.

Moreover, the frequent occurrence of keywords such as “mortality,” “biomarkers,” and “electronic health records” reflects a multidisciplinary orientation that combines AI techniques with clinical diagnostic processes. Analytical approaches including logistic regression, neural networks, and nomogram-based models are commonly applied in model construction, indicating a shift from purely conceptual development toward practical implementation in real-world ICU environments. Supporting this progression, prior studies have demonstrated that machine learning algorithms are capable of predicting sepsis up to 12 hours before clinical onset (11), and systems such as the NAVOY Sepsis model have shown promising proof-of-concept performance in intensive care contexts (6).

Nevertheless, despite the considerable potential of artificial intelligence, only a limited number of predictive models have undergone sufficient validation for routine clinical application. Factors such as heterogeneity in data sources, limited model transparency and interpretability, and regulatory constraints continue to impede broad implementation (9,12,13). Furthermore, a substantial proportion of AI-driven sepsis research relies on retrospective datasets and lacks rigorous external validation, which restricts the generalizability of reported findings.

When the expansion rate of AI-focused sepsis studies (31.19%) is compared with bibliometric patterns observed in other intensive care conditions, including pneumonia and cardiac arrest (20,36,37), a broadly comparable growth pattern emerges. However, research on AI applications in sepsis demonstrates a notably sharper increase over the past five years. This accelerated growth indicates that sepsis may function as a sentinel condition, signaling broader innovation and adoption of artificial intelligence within the critical care domain.

According to the results of this analysis, Das R. was identified as the most productive author in this research field, while Scientific Reports was recognized as the leading journal in terms of influence. Together, these findings highlight key contributors and publication platforms that play a central role in shaping the development and dissemination of AI-based sepsis research.

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, restricting the data source to the Web of Science database may have led to the omission of relevant publications indexed in other repositories, such as PubMed, Scopus, or leading artificial intelligence–oriented conference proceedings. This restriction may have resulted in selection bias, favoring certain journals and geographic regions. Additionally, while bibliometric approaches are effective for examining publication patterns and citation performance, they do not provide an assessment of the methodological rigor or the clinical effectiveness of individual studies.

In summary, the present analysis offers a systematic depiction of research focal points and developmental trends in AI-supported sepsis research within intensive care units. The growing focus on predictive analytics, early detection strategies, and clinical decision support systems suggests a trajectory in which artificial intelligence may substantially influence future sepsis management. Nonetheless, further prospective investigations and validation studies conducted in real-world clinical settings are essential to close the gap between technological advancement and practical implementation in routine care.

Study limitations and strengths

The most important limitation of this study is that the literature review is limited to the data obtained from the WoS database. Another limitation is that the publications belong to the time period between 2006 and 2025 when the literature review was conducted. If a similar study is conducted in a different time period, different results may be obtained. Apart from the limitations, the study also has some strengths. The current study shows that publications can achieve a high level of visibility even in subspecialty journals. This once again emphasizes the potential value of the methodology used in the study, as further examination of publications outside of high-impact publications that receive high levels of attention could help researchers to better understand how to promote their work. Furthermore, the interaction with sources reflected in the bibliometric analysis result could support the creation of potential studies for researchers if grant funders start to take them into account despite the acknowledged limitations.

Conclusion

This study provides important data on sepsis and artificial intelligence applications in intensive care units. The results of the bibliometric analysis show that studies in this field are extremely recent. Studies on sepsis and artificial intelligence in intensive care units between 2006 and 2025 have been included in the literature. The number of publications has increased steadily since 2019, reaching its highest number in 2024. After the COVID-19 pandemic, sepsis and artificial intelligence applications have emerged as an important field of study. Recent studies have focused on clinical models, decision support systems, and machine learning. While studies in the fields of mortality, sepsis, and intensive care were prevalent in the early days, in recent years, studies using keywords such as machine learning, clinical decision support, output, big data, artificial intelligence machine learning, sepsis, and COVID-19 have become more common. Therefore, the results of this study are quite important in guiding researchers regarding gaps in the literature. It is thought that the results obtained in this study can evaluate the current situation in intensive care units in the field of sepsis and artificial intelligence, provide a general overview of the field, and guide future research in this area.

There are gaps between research and clinical application of AI-based sepsis prediction models. To bridge these gaps; it is recommended that prospective clinical studies be conducted to evaluate AI-sepsis models, that AI models that include multimodal data (e.g. vital signs, genomics, imaging) be developed, and that ethical concerns and explainability of AI be addressed in the clinical decision-making process.

Ethical approval

This study includes a retrospective review of previously published studies and their visualization by bibliometric analysis. The study did not involve any human or animal study. Therefore, this study does not require ethics committee approval.

Source of funding

The authors declare the study received no funding.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What is sepsis? Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/sepsis/about/index.html (Accessed on November 27, 2023).

- Rhee C, Jones TM, Hamad Y, et al. Prevalence, underlying causes, and preventability of sepsis-associated mortality in US acute care hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e187571. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.7571

- Rudd KE, Johnson SC, Agesa KM, et al. Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990-2017: analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 2020;395:200-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32989-7

- Liu V, Escobar GJ, Greene JD, et al. Hospital deaths in patients with sepsis from 2 independent cohorts. JAMA. 2014;312:90-2. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.5804

- Reinhart K, Daniels R, Kissoon N, Machado FR, Schachter RD, Finfer S. Recognizing Sepsis as a Global Health Priority - A WHO Resolution. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:414-7. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1707170

- Persson I, Östling A, Arlbrandt M, Söderberg J, Becedas D. A machine learning sepsis prediction algorithm for intended intensive care unit use (NAVOY Sepsis): proof-of-concept study. JMIR Form Res. 2021;5:e28000. https://doi.org/10.2196/28000

- Al-Mualemi BY, Lu L. A deep learning-based sepsis estimation scheme. IEEE Access. 2021;9:5442-52. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3043732

- Schinkel S, Schouten BC, Kerpiclik F, Van Den Putte B, Van Weert JCM. Perceptions of barriers to patient participation: are they due to language, culture, or discrimination? Health Commun. 2019;34:1469-81. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2018.1500431

- Yuan KC, Tsai LW, Lee KH, et al. The development an artificial intelligence algorithm for early sepsis diagnosis in the intensive care unit. Int J Med Inform. 2020;141:104176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2020.104176

- Alanazi A, Aldakhil L, Aldhoayan M, Aldosari B. Machine learning for early prediction of sepsis in intensive care unit (ICU) patients. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59:1276. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59071276

- Nemati S, Holder A, Razmi F, Stanley MD, Clifford GD, Buchman TG. An interpretable machine learning model for accurate prediction of sepsis in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:547-53. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000002936

- Burdick H, Pino E, Gabel-Comeau D, Gu C, Huang H, Lynn-Palevsky A, Das R. Evaluating a sepsis prediction machine learning algorithm in the emergency department and intensive care unit: a before and after comparative study. BioRxiv. 2017:224014. https://doi.org/10.1101/224014

- Moor M, Rieck B, Horn M, Jutzeler CR, Borgwardt K. Early prediction of sepsis in the ICU using machine learning: a systematic review. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:607952. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.607952

- Islam MM, Nasrin T, Walther BA, Wu CC, Yang HC, Li YC. Prediction of sepsis patients using machine learning approach: A meta-analysis. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2019;170:1-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2018.12.027

- Fleuren LM, Klausch TLT, Zwager CL, et al. Machine learning for the prediction of sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:383-400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-019-05872-y

- Esen M, Bellibas MS, Gumus S. The evolution of leadership research in higher education for two decades (1995-2014): a bibliometric and content analysis. International Journal of Leadership in Education. 2020;23(3):259-73. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2018.1508753

- Moral-Munoz JA, Herrera-Viedma E, Santisteban-Espejo A, Cobo MJ. Sofware tools for conducting bibliyometric analysis in sience: An -up-to-date rewiew. El Profesional de La Informacion. 2020;29(1):273-89. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2020.ene.03

- Guleria D, Kaur G. Bibliometric analysis of ecopreneurship using VOSviewer and R Studio Bibliometrix, 1989-2019. Library Hi Tech. 2021;1(24):1001-24. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHT-09-2020-0218

- Karagöz B, Şeref İ. Bibliometric profile of Journal of Values Education (2009-2018). Journal of Values Education. 2019;17(37):219-46. https://doi.org/10.34234/ded.507761

- Ramos-Rincón JM, Pinargote-Celorio H, Belinchón-Romero I, González-Alcaide G. A snapshot of pneumonia research activity and collaboration patterns (2001-2015): a global bibliometric analysis. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19:184. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0819-4

- Zavadskas EK, Skibniewski MJ, Antucheviciene J. Performance analysis of civil Engineering Journals based on the web of science® database. Archives of Civil and Mechanical Engineering. 2014;14(4):519-27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acme.2014.05.008

- Zhu J, Song LJ, Zhu L, Johnson RE. Visualizing the landscape and evolution of leadership research. The Leadership Quarterly. 2019;30(2):215-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.06.003

- Waltman L, Van Eck NJ. A smart local moving algorithm for large-scale modularity-based community detection. The European Physical Journal B. 2013;86(11):1-14. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjb/e2013-40829-0

- Aria M, Cuccurullo C. Bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. Journal of Informetrics. 2017;11(4):959-75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2017.08.007

- Mingers J, Leydesdorff L. A review of theory and practice in scientometrics. European Journal of Operational Research. 2015;246(1):1-19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2015.04.002

- van Eck NJ, Waltman L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics. 2010;84:523-38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-009-0146-3

- Chen C. CiteSpace II: Detecting and visualizing emerging trends and transient patterns in scientific literature. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 2006;57(3):359-77. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20317

- Börner K, Chen C, Boyack KW. Visualizing knowledge domains. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology. 2003;37(1):179-255. https://doi.org/10.1002/aris.1440370106

- López-Robles JR, Cobo MJ, Gutiérrez-Salcedo M, Martínez-Sánchez MA, Gamboa-Rosales NK, Herrera-Viedma E. 30th anniversary of applied intelligence: a combination of bibliometrics and thematic analysis using SciMAT. Applied Intelligence. 2021;51(9):6547-68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10489-021-02584-z

- Sott MK, Bender MS, Furstenau LB, Machado LM, Cobo MJ, Bragazzi NL. 100 years of scientific evolution of work and organizational psychology: A bibliometric network analysis from 1919 to 2019. Front Psychol. 2020;11:598676. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.598676

- Bradford SC. Sources of information on specific subjects. Engineering: An Illustrated Weekly Journal. 1943;137:85-6.

- Bradford SC. Information sources on specific topics. Journal of Information Science. 1985;10(4):173-80. https://doi.org/10.1177/016555158501000406

- Jabaley CS, Groff RF, Stentz MJ, et al. Highly visible sepsis publications from 2012 to 2017: Analysis and comparison of altmetrics and bibliometrics. J Crit Care. 2018;48:357-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.09.033

- Zhang Z, Van Poucke S, Goyal H, Rowley DD, Zhong M, Liu N. The top 2,000 cited articles in critical care medicine: a bibliometric analysis. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10:2437-47. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2018.03.178

- Rosenberg AL, Tripathi RS, Blum J. The most influential articles in critical care medicine. J Crit Care. 2010;25:157-70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2008.12.010

- Tao T, Zhao X, Lou J, et al. The top cited clinical research articles on sepsis: a bibliometric analysis. Crit Care. 2012;16:R110. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc11401

- Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The third international consensus definitions for Sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315:801-10. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.0287

Copyright and license

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is properly cited.