Abstract

Objective: We aimed to evaluate the characteristics, prognosis, laboratory parameters, and mortality of severely ill obstetric patients due to severe COVID-19 disease and determine the factors affecting mortality.

Methods: Medical records of obstetric patients with COVID-19 infection were reviewed. Patients were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) and the outcomes of the newborns were evaluated furtherly.

Results: A total of 325 women were included. The ICU requirement was 8.6% (28/325). Among 28 women admitted to ICU maternal mortality rate was 53.6% (15/28), and preterm delivery rate was 88% (24/28). The 27 newborns were evaluated furtherly. Six stillbirths occurred. 40.7% (11/27) of the newborns had 1st minute APGAR scores lower than 7, while 33.3% (9/27) of them had 5th minute APGAR scores lower than 7. Body mass index, CRP, D-dimer, LDH, and CRP/Alb ratio were found to be significantly higher in the mortality cohort than surviving women requiring ICU. The CRP/Alb ratio was the most significant predictor of COVID-19-related maternal death in ICU.

Conclusion: The study revealed that COVID-19-related maternal mortality is considerably high in severely ill patients. The CRP/Alb ratio is a significant predictor of mortality. The cesarean section and preterm delivery rates were significantly high in severely ill mothers with COVID-19. Additionally, the severity of the mothers’ illness negatively influenced neonatal outcomes.

Keywords: COVID-19, intensive care unit, mortality, obstetric

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the new coronavirus disease (COVID-19) as an epidemic on March 11, 2020, and the first case of COVID-19 was detected in our country on the same date (1). By May 2022, WHO had announced more than 517.648.631 confirmed cumulative cases and approximately 6.261.708 cumulative deaths (2). On the same date, Turkey, reported more than 15.050.207 confirmed cumulative cases and about 98.878 cumulative deaths (2).

While the course of COVID-19 disease can be asymptomatic, it can also present a clinical manifestation that can range from mild symptoms to respiratory failure or multi-organ failure (1,3). Although yielding data provide us a point of view regarding the characteristics of COVID-19 infection in the general population, there are very little data exist in terms of risk factors concerning COVID-19 disease in specific patient groups, such as obstetric patients (4). Previous pandemics reports revealed that COVID-19 infection in pregnant women was associated with an increased risk for complications (5). After then, Li et al. (4) stated the COVID-19 disease usually presented mild respiratory symptoms in pregnant women, predominantly together with fever and pneumonia; on the other hand, other severe respiratory symptoms were reported to be less common. Furthermore, Antoun et al. (6) suggested that COVID-19 disease could lead to an increase in the prevalence of preterm birth, preeclampsia, and cesarean section, without increasing severe complications in newborns. Finally, it was concluded in another report that, despite the generally mild or asymptomatic course of COVID-19 disease in young patients, the risk of severe and complicated illness was higher in the pregnant population of the same age (7).

Although several studies are conducted in the general population researching the clinical and laboratory parameters predicting the progression to severe disease in COVID-19, the data are very few in obstetric patients. Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the characteristics, prognosis, laboratory parameters, and mortality of obstetric patients followed up in the intensive care unit (ICU) due to severe COVID-19 disease and to determine the factors affecting mortality.

Materials and Methods

The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and registered to www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT05264987). After the approval of the local ethics committee (2011-KAEK-25 2021/06-20), obstetric patients hospitalized in the ICU of Bursa Yuksek Ihtisas Training and Research Hospital between March 11, 2020 - September 15, 2021, were reviewed retrospectively. Patients admitted to the ICU for COVID-19 during the pregnancy and postpartum period, from the beginning of pregnancy and up to 42 days after delivery, were included in the study. Patients with clinically suspected COVID-19 disease and having negative PCR tests were excluded from the study.

Demographic data, obstetric histories, comorbidities, treatments received in the ICU, delivery types, anesthesia types, and outcomes of newborns and mothers were retrospectively evaluated from the medical records. The need for the mechanical ventilator, the length of stay in the ICU, and outcomes of mothers were recorded. Laboratory findings were noted on the first day of admission to the ICU, including routine complete blood count, liver and kidney function, coagulation parameters, C-reactive protein (CRP), and albumin levels. Then neutrophil to lymphocyte (N/L) ratio, platelet to lymphocyte (P/L) ratio, and CRP to albumin (CRP/Alb) ratio were calculated. Deceased patients were evaluated in detail, and extreme cases were discussed.

The data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics for Windows version 19.0, 2010 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). The Fisher’s exact test was conducted to analyze categorical variables. Non-parametric tests were performed to analyze the small sample-sized data (n<30). The continuous maternal variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney-U test. The maternal characteristics and laboratory tests were presented as median (25-75 percentiles) and number (%). Poor neonatal outcomes were determined as 1st and 5th minute APGAR scores lower than 7, and poor maternal outcomes were identified as maternal death. The relation of the contributing factors with poor neonatal outcomes was analyzed using the Spearman correlation test. The statistically significant parameters in the maternal death were included in a further logistic regression model. After the multicollinearity analysis (tolerance >0.4), the Hosmer-Lemeshow test was performed to check the model’s fitness. The effect sizes were presented as odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Additionally, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was conducted to find out optimal cut-off level and sensitivity and specificity of the demonstrated cut-off value of the independent parameters associated with maternal mortality. All tests were performed as two-tailed, and p<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Ward patients

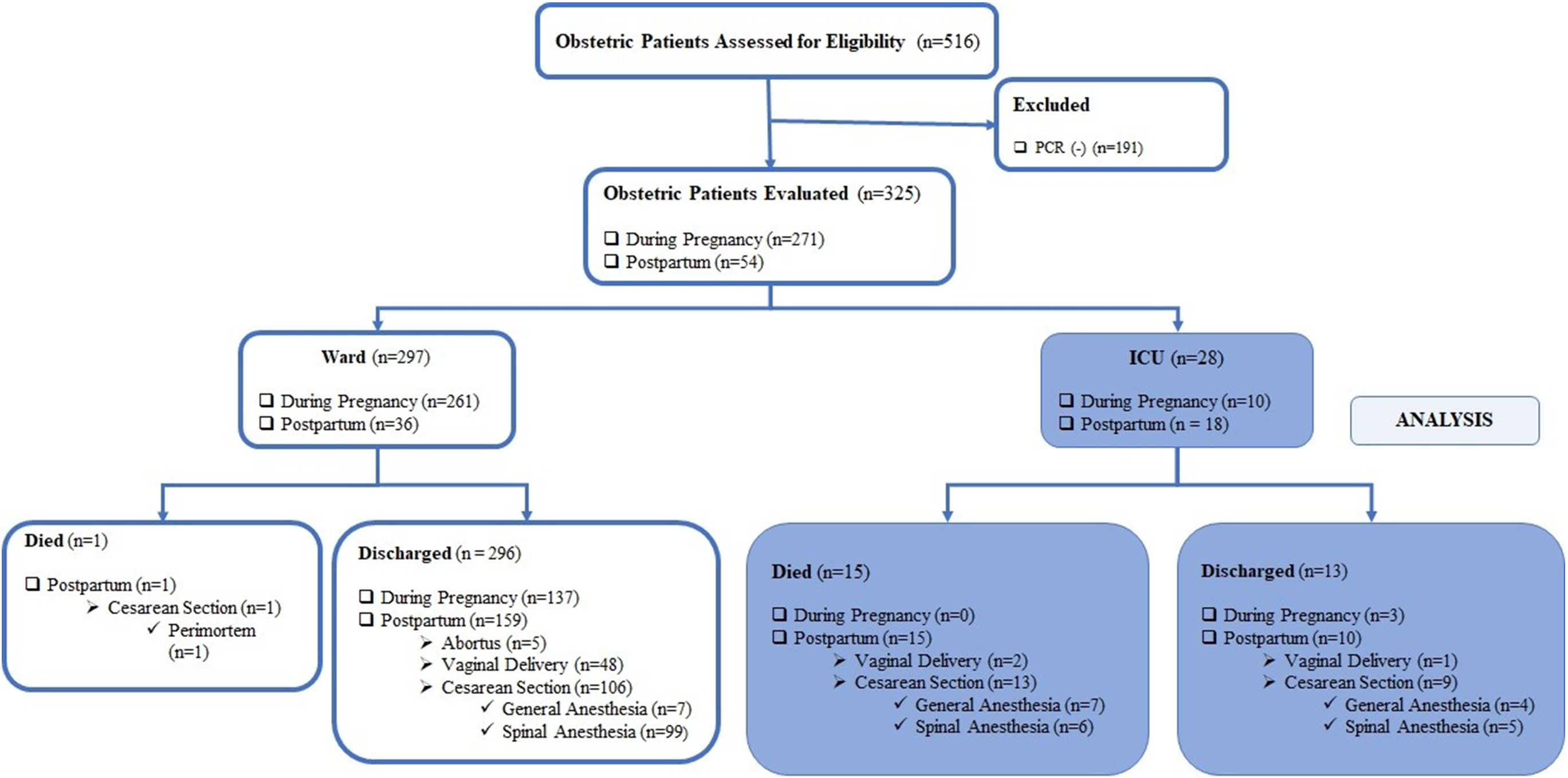

During the time process of this study, 516 patients were admitted to the COVID-19 obstetrics ward, and 325 patients with positive SARS CoV-2 PCR tests were included in the analysis. Of these, 271 (83.9%) were hospitalized during pregnancy, and 54 (16.6%) in the postpartum period. 296 (91.1%) of the hospitalized patients were discharged well from the hospital, 28 (8.61%) patients required admission to the ICU, and one died in the obstetrics ward. Of the 296 discharged patients, 137 patients were discharged with an ongoing pregnancy and 159 in the postpartum period. Of the159 postpartum patients, five aborted, 106 were delivered by cesarean section (general anesthesia rate 6.6% and spinal anesthesia rate 93.4%), and 48 were delivered vaginally (Figure 1).

The rate of asymptomatic patients at the time of admission to the hospital was 10.7%. Dyspnea 21.4%, cough 14.3%, anosmia and ageusia 3.6%, and vomiting 3.6% were observed in patients. Only one of our patients had received the COVID-19 vaccine. She was hospitalized and discharged during her pregnancy.

The Code Blue Case in the Obstetrics Ward

The case was a 35-years-old, 27 gestational weeks pregnant woman with no comorbidity who was being followed up in the obstetric ward. Due to respiratory distress, the patient was intubated in the ward following the Code Blue emergency call. Then a sudden cardiac arrest was developed just before the transfer to the ICU. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation was immediately started, and a perimortem cesarean section was performed. A living neonate was delivered, with the 1st minute APGAR score of 0 and the 5th minute APGAR score of 4. This newborn was excluded from the neonatal outcomes analysis.

Difficult Airway in a Morbid Obese Patient

The case was a 25-years-old morbid obese patient with a BMI of 49.2 kg/m2. The patient was consulted with the Anesthesiology and Reanimation team due to severe respiratory distress on the third postpartum day. The consultant team considered transferring the patient to ICU; however, it was decided to secure the airway first in the ward before the transfer because of the severe dyspnea. Both mask ventilation and intubation of this patient were difficult. Intubation was possible in the third attempt with gum elastic bougie. Seven healthcare personnel were infected with SARS-CoV-2 from the patient despite wearing Level-3 personal protective equipment. At that time, vaccination had not yet started in our country.

ICU patients

A total of 28 women were admitted to the ICU. Of these patients, 18 (64.29%) were postpartum patients, and 10 (35.71%) had ongoing pregnancies. The criteria for admission to ICU were respiratory rate ≥30 breaths per minute, oxygen saturation level ≤90%, and Horowitz index ≤300 mmHg. The maternal characteristics and the comparison of the data between mortality and survival patients were presented in Table 1. The comparison of the laboratory parameters at first admission to the ICU was presented in Table 2.

| Categorical variables are presented as n (%), continuous variables are presented as median (25–75 percentiles); APACHE II: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation-II, BMI: Body mass index, ICU: Intensive care unit; *p<0.05; †Number of patients who delivered only by cesarean section. | ||||

| Table 1. Demographic data of the cases admitted to the ICU | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Age, years |

|

|

|

|

| BMI, kg/m2 |

|

|

|

|

| Gravidity, n |

|

|

|

|

| Parity, n |

|

|

|

|

| Gestational weeks, weeks |

|

|

|

|

| APACHE II, points |

|

|

|

|

| Comorbid diseases, yes |

|

|

|

|

| Pregnancy-induced hypertensive diseases |

|

|

|

|

| Cardiac diseases |

|

|

|

|

| Diabetes mellitus |

|

|

|

|

| Substance abuse |

|

|

|

|

| Trimester, n |

|

|||

| 1st trimester |

|

|

|

|

| 2nd trimester |

|

|

|

|

| 3rd trimester |

|

|

|

|

| Birth, n |

|

|||

| None |

|

|

|

|

| Vaginal |

|

|

|

|

| Cesarean section |

|

|

|

|

| Anesthesia†, n |

|

|||

| General anesthesia |

|

|

|

|

| Regional anesthesia |

|

|

|

|

| The results are presented as median (25–75 percentiles). CRP/Alb: C-Reactive Protein/Albumin, ICU: Intensive care unit, N/L: Neutrophil/lymphocyte, P/L: Platelet/lymphocyte. | ||||

| Table 2. Laboratory parameters at initial admission to the ICU | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Hemoglobin, g/dL |

|

|

|

|

| White Blood Cell, mcl |

|

|

|

|

| Neutrophil count, ×103/mL |

|

|

|

|

| Lymphocyte count, ×103/mL |

|

|

|

|

| Platelet, mcl |

|

|

|

|

| Aspartate Aminotransferase, U/L |

|

|

|

|

| Alanine Aminotransferase, U/L |

|

|

|

|

| Blood Urea Nitrogen, mg/dL |

|

|

|

|

| Creatinine, mg/dL |

|

|

|

|

| C-Reactive Protein, mg/L |

|

|

|

|

| Fibrinogen, mg/dL |

|

|

|

|

| D-dimer, mg/mL |

|

|

|

|

| Ferritin, ng/mL |

|

|

|

|

| Lactate Dehydrogenase, U/L |

|

|

|

|

| Albumin, g/L |

|

|

|

|

| N/L ratio |

|

|

|

|

| P/L ratio |

|

|

|

|

| CRP/Alb ratio |

|

|

|

|

While 16 of our cases were followed up with high-flow nasal oxygen therapy, 22 patients were intubated due to refractory hypoxemia and needed invasive mechanical ventilation. The requirement for mechanical ventilation was 82.14% (n=23) in all our obstetric COVID-19 ICU patients. All the postpartum patients were placed in the prone position. Also, the other pregnant patients were placed in the prone position after delivery. The median (25-75 percentiles) length of stay in the ICU was 10.0 (4.0 – 15.0) days, and the median (25-75 percentiles) number of days spent on the mechanical ventilator was 4.0 (1.0 – 10.8) days.

A massive pulmonary embolism developed in a patient on the 6th day in the ICU despite thrombolytic therapy; then, she died in the ICU on the same day.

Outcomes of patients discharged from the ICU during pregnancy

We were able to discharge three patients to the obstetrics ward with an ongoing pregnancy. One of these patients gave birth by cesarean section under epidural anesthesia six weeks after discharge, and the other delivered vaginally eight weeks later. The records of the last patient could not be accessed because she did not give birth in our hospital.

Maternal mortality

The mortality rate of obstetric patients admitted to the ICU due to COVID-19 disease was found to be 53.57% (15/28). The all-over mortality rate of the hospitalized obstetric patients with COVID-19 disease was found to be 4.92% (16/325).

Factors that influence maternal mortality

The body mass index (BMI) was significantly higher in patients who died than survived patients (p=0.019). Cesarean section was performed in 22 of our cases, and general anesthesia was applied at a rate of 50%. The reasons for preferring general anesthesia were low platelets, cardiac causes, severe respiratory distress, and one case previously intubated in the ICU.

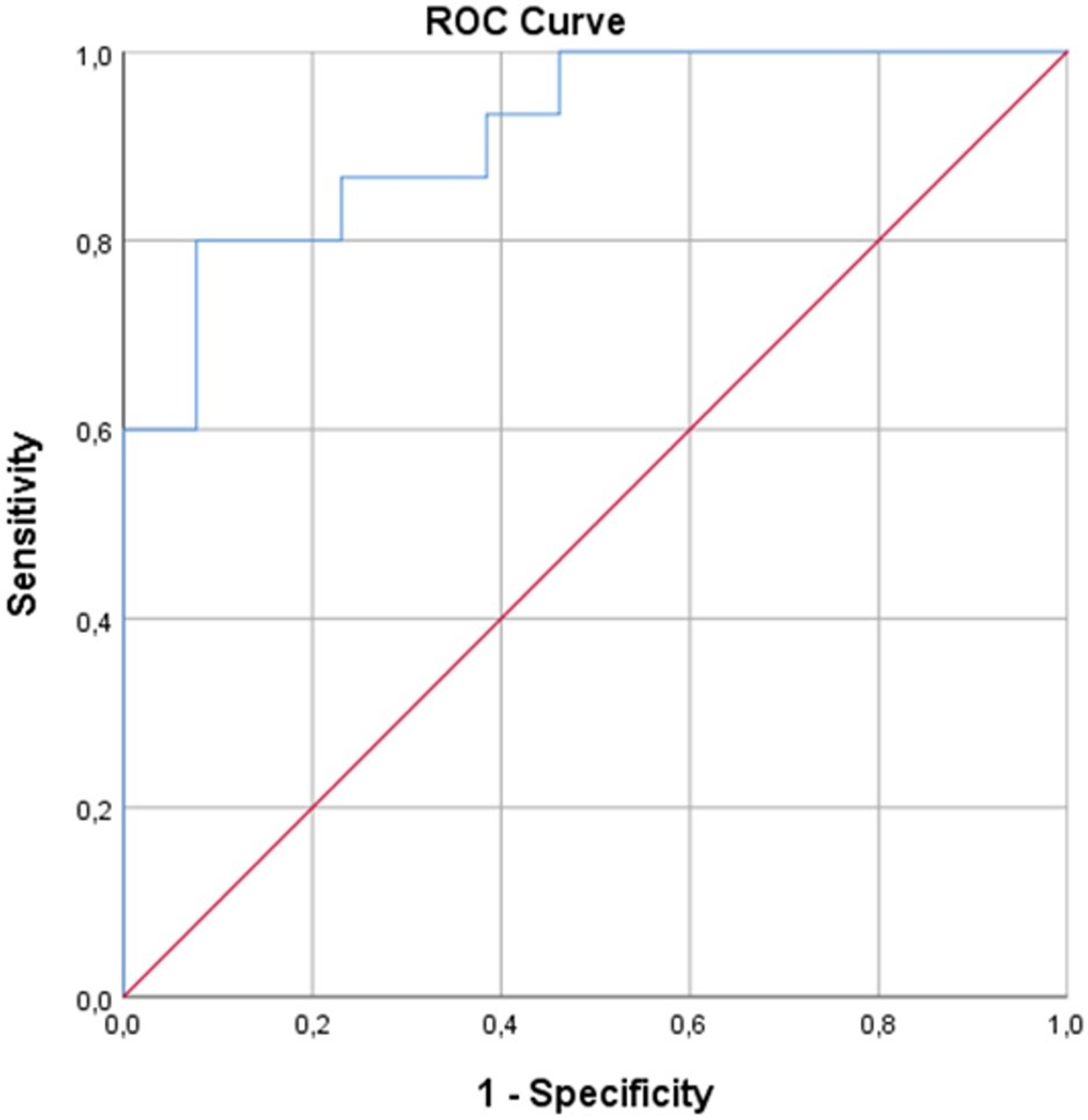

Among these, CRP (p<0.001), D-dimer (p=0.013), LDH (p=0.006), and CRP/Alb ratio (p<0.001) were found to be significantly higher in the mortality cohort than survival cohort. After then, BMI, D-dimer, LDH, and CRP/Alb ratio were included in further logistic regression analysis. The CRP was excluded from the final analysis due to the CRP/Alb ratio co-linearity. The model’s fitness was verified with the Hosmer-Lemeshow test. The final model explained 79.8% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in maternal death and correctly classified 85.7% of the cases (sensitivity: 86.7%, specificity: 84.6%). Accordingly, CRP/Alb ratio was found as the most significant predictor of COVID-19 maternal death in ICU (OR, [95% CI]: 6.924, [1.174 – 40.841]; p=0.033) (Table 3). Finally, the discriminative power for COVID-19 maternal death in ICU of CRP/Alb ratio was evaluated using ROC analysis (Figure 2). The AUC [95% CI] for prediction of mortality for CRP/Alb ratio was found to be 0.913 [0.811 – 1.000]; p<0.001. The cut-off value for predicting maternal mortality of CRP/Alb ratio was calculated as 3.99 with a sensitivity of 80.0% and specificity of 92.3%.

| BMI: Body mass index, CRP/Alb: C-Reactive Protein/Albumin. | |||

| Table 3. Logistic regression analysis of risk factors in died patients | |||

|

|

|

|

|

| BMI |

|

|

|

| Lactate Dehydrogenase |

|

|

|

| D-dimer |

|

|

|

| CRP/ Alb ratio |

|

|

|

Neonatal outcomes

Two women gave birth to twins. Accordingly, a total of 27 newborns born from 25 mothers were included in the further analysis. The preterm delivery rate (<37 gestational weeks) was 88.0%. Six stillbirths occurred. The rate of the newborns having 1st minute APGAR scores lower than 7 was 40.7% (11/27), while the rate of the newborns having 5th minute APGAR scores lower than 7 was 33.3% (9/27). All newborns tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 with nasopharyngeal swabs. No congenital anomaly was observed in any of the newborns. The mean weight of newborn babies was 1985.96 ± 1050.72 kg; additionally, 59.3% of the newborns were girls, 40.7% were boys.

Factors that influence neonatal outcomes

Factors that influence neonatal outcomes were evaluated with correlation analysis (Table 4). Accordingly, low neonatal birth weight was moderately correlated with 1st minute APGAR scores lower than 7 (r=-0.643; p=0.000) and strongly correlated with 5th minute APGAR scores lower than 7 (r=-0.589; p=0.002). Furthermore, being in the second trimester and early gestational weeks were strongly correlated with 1st and 5th minute APGAR scores lower than 7 (Table 4).

| APACHE-II: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation-II, BMI: Body mass index. | ||||

| Table 4. The correlation of 1st and 5th minute APGAR scores with neonatal and maternal factors. | ||||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Neonatal factors | ||||

| Weight, kg |

|

|

|

|

| Trimester, 3rd |

|

|

|

|

| Gestational weeks, weeks |

|

|

|

|

| Maternal factors | ||||

| Age, years |

|

|

|

|

| BMI, kg/m2 |

|

|

|

|

| Gravidity, n |

|

|

|

|

| Parity, n |

|

|

|

|

| Comorbidity, yes |

|

|

|

|

| Perinatal complication, yes |

|

|

|

|

| APACHE-II, score |

|

|

|

|

| Death, yes |

|

|

|

|

Discussion

This report presented the outcomes of obstetric patients with confirmed COVID-19 disease admitted to the hospital. Additionally, the 28 obstetric patients requiring ICU follow-up and the newborns of these patients were evaluated furtherly. We found the mortality rate of obstetric patients due to COVID-19 disease in ICU as 53.57%. The cesarean section rate in severely ill obstetric patients was 78.57%. The BMI, CRP, D-dimer, LDH, and CRP/Alb ratio were significantly high in the mortality cohort. Among these parameters, the CRP/Alb ratio was found to be the most significant predictor of maternal death related to COVID-19 disease in the ICU. The cut-off value for predicting maternal mortality of CRP/Alb ratio was calculated as 3.99 with a sensitivity of 80.0% and specificity of 92.3%.

Although it is well documented that infectious diseases can cause varying degrees of both maternal and neonatal complications in the pregnant patient group, it was a matter of curiosity to what extent and how COVID-19 would affect pregnant women at the onset of the pandemic. The presented data in the later pandemic stages have shown that the mortality rate due to infection varied in a wide range between 0.3-12.7% in obstetric patients with positive SARS CoV-2 PCR test (8-15). However, the indications for admission to the ICU and the inclusion criteria of the patients in these reports varied widely, which could explain the high variability in mortality rates. While the mortality rate decreased with the inclusion of asymptomatic or patients with mild symptoms in the analysis, this rate increased when only the patients admitted to the ICU were evaluated. Accordingly, the results of our study indicated the mortality rate of test-positive pregnant women ranged from 4.92% to 53.57%.

Andrikopoulou et al. (16) reported in their study that one in five of the COVID-19 obstetric patients developed moderate or severe symptoms, while ten patients required respiratory support without intubation. Additionally, they stated the only patient was intubated for general anesthesia for cesarean section (16). Also, a previous report suggested that 67.2% of patients undergoing cesarean section were asymptomatic, and 14% had pneumonia (17). In our study, the rate of asymptomatic patients at the time of admission to the hospital was 10.7%, and severe disease requiring ICU was 8.61%, while the remaining had mild to moderate disease. All pregnant women with moderate disease followed up in the COVID-19 Obstetrics ward received respiratory support with a nasal cannula or nonrebreather mask. Patients who needed high flow oxygen or mechanical ventilatory respiratory support in addition to the previously mentioned ICU-admission criteria were followed up in the ICU. 78.57% of our patients were intubated in the ICU. Akinosoglou et al. (18) studied 60 pregnant women who presented to the emergency department with COVID-19 and reported that none of the patients survived the pregnancy and 6.6% required invasive mechanical ventilation.

Although no vertical transmission of SARS CoV-2 has been reported in any of the studies conducted until April 2020, the possibility of a vertically-transmitted illness started to be mentioned in the reports up to August 2020 (19,20). Significantly; the third trimester has been emphasized as the most unprotected period for infection (19). Oncel et al. (12) stated that COVID-19 was a risk for maternal death, vertical transmission, and neonatal disease. Additionally, the authors reported 3.3% (4/120) of newborns had tested positive for SARS CoV-2 (12). However, none of the newborns delivered from any of the COVID-19 positive mothers had positive PCR results in our study. It was postulated in a study that symptomatic parturients with COVID-19 were at increased risk of preterm birth, cesarean section, and peripartum ICU admission (21). In this report, the preterm delivery rate of parturients with severe disease was 88.0% (22 of the 25 patients), and six were stillbirths. While 40.7% (11/27) newborns had low 1st minute APGAR scores, 33.3% (9/27) had low 5th minute APGAR scores.

Takemoto et al. (13) indicated that 48.4% of fatal cases had at least one comorbidity and suggested postpartum ARDS, obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease were the main risk factors for COVID-19-related maternal deaths. Also, they asserted that white ethnicity provided a protective effect (13). Additionally, Hazari et al. (10) pointed out that half of their pregnant COVID-19 ICU patients had BMI higher than 30 kg/m2. Moreover, Chu et al. (22) concluded in their meta-analysis that obesity was strongly associated with poor outcomes of COVID-19, including increased ICU admissions, mechanical ventilation support, and disease progression. Similarly, the BMI was significantly higher in dead patients than the survived patients in our study.

Many clinical parameters and laboratory tests have been evaluated in the general population to predict the progression to severe COVID-19 disease. Ganesan et al. (23) showed Charlson comorbidity index, sequential organ failure assessment score, D-dimer, LDH, and N/L ratio were independently associated with mortality in COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU. Ozer et al. (24) reported hypertension, malignancy (solid and hematological), neurological disease, age, APACHE-II and SOFA scores, and N/L ratio as factors affecting mortality in patients with COVID-19 in ICU. Subsequently, Li Y et al. (25) reported a higher N/L ratio, P/L ratio, CRP/Alb ratio, and systemic immune-inflammation index in those with progressive disease than those with stable disease. Moreover, they demonstrated a CRP/Alb ratio greater than 1.843 was closely associated with higher hospital mortality rates, ICU admission, invasive mechanical ventilation, and longer hospital stays. In our study, the CRP/Alb ratio was found as the most significant predictor of COVID-19 maternal death in the ICU. The cut-off value of the CRP/Alb ratio was calculated as 3.99 with a sensitivity of 80.0% and specificity of 92.3%.

Pregnant patients tend to have difficult airways due to increased oropharyngeal edema; thus, preparations should be made accordingly. We observed difficult mask ventilation in a case with a BMI of 49.2 kg/m2 and both difficult mask ventilation and intubation in the ward. Mask ventilation of those patients was possible with two practitioners. The case was intubated with gum elastic bougie in the third attempt. Even though all the team members helping the management of the intubation case wore Level-3 personal protective equipment, the disease was transmitted to seven of the nine staff.

During the worldwide spread of the COVID-19, regional anesthesia techniques are encouraged over aerosol-generating procedures (26). Moreover, the benefits of regional anesthesia in the cesarean section are well-known. However, the risk and benefit balance should be tailored for the patients individually. In a previous study on COVID-19 positive patients delivering by cesarean section, the general anesthesia rate was 4.9% (17). Nevertheless, in this report handling the obstetric COVID-19 ICU patients, the general anesthesia rate in patients undergoing cesarean section was found to be 50%, while the overall general anesthesia rate for cesarean section in COVID-19 patients was 14.06%. The choice of anesthesia technique may vary depending on viral contamination, the clinical condition of the patient, and the clinical experience and expertise of the anesthesiologist.

Dashraath et al. (27) suggested that pregnant women with COVID-19 infection are at a higher risk of thromboembolic disorders during the third trimester. After then, Goudarzi et al. (28) published a case report of maternal death due to pulmonary embolism during COVID-19 infection. In one case of our report, despite receiving antithrombotic therapy, a massive pulmonary embolism developed on the 6th day of her admission to the ICU; then, she died on the same day.

Vaccination rates among pregnant women vary by region. The vaccination rate among pregnant women was low in our country when vaccination was first started. But, the vaccination rate in pregnant women began to increase as the pandemic spread. Only one of our patients presented in this report had received the COVID-19 vaccine. After two days of high flow oxygen treatment, this vaccinated patient was discharged from the ICU. Pecks et al. (29) reported that vaccinated pregnant women required less hospitalization for COVID-19 than unvaccinated women.

The strength of this study was the relatively large sample size enough to comment on the overall COVID-19-related maternal morbidity and mortality. Additionally, the presented extreme cases set up examples of the challenging situations that may be encountered in pregnant women with COVID-19. On the other hand, its retrospective nature was a weakness of the study. The small sample size of the ICU patients included in the further evaluation might fail to demonstrate modest differences.

In conclusion, this study found the overall COVID-19-related maternal mortality rate as 4.92%, but this rate rose to 53.57% among patients requiring ICU care. The BMI, CRP, D-dimer, LDH, and CRP/Alb ratio were the independent predictors of mortality; besides, the CRP/Alb ratio was the strongest predictor of mortality in severely ill obstetric patients with COVID-19. The cesarean section and preterm delivery rates were significantly high in severely ill mothers with COVID-19. Additionally, the severity of the mothers’ illness negatively influenced neonatal outcomes.

Ethical approval

This study has been approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (2011-KAEK-25 2021/06-20). The trial was also retrospectively registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05264987). Patient informed consent was waived due to the retrospective study design. Researchers analyzed only anonymized data.

Source of funding

The authors declare the study received no funding.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Q&A on coronaviruses (COVID-19). 2022. Available at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 (Accessed on May 16, 2022).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Coronavirus (COVID-19). 2022. Available at: https://covid19.who.int/ (Accessed on May 16, 2022).

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497-506. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5

- Li N, Han L, Peng M, et al. Maternal and neonatal outcomes of pregnant women with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia: a case-control study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:2035-41. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa352

- Jamieson DJ, Honein MA, Rasmussen SA, et al. H1N1 2009 influenza virus infection during pregnancy in the USA. Lancet. 2009;374:451-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61304-0

- Antoun L, Taweel NE, Ahmed I, Patni S, Honest H. Maternal COVID-19 infection, clinical characteristics, pregnancy, and neonatal outcome: a prospective cohort study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;252:559-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.07.008

- Celewicz A, Celewicz M, Michalczyk M, et al. Pregnancy as a risk factor of severe COVID-19. J Clin Med. 2021;10:5458. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10225458

- Papapanou M, Papaioannou M, Petta A, et al. Maternal and neonatal characteristics and outcomes of COVID-19 in pregnancy: an overview of systematic reviews. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:596. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020596

- Metz TD, Clifton RG, Hughes BL, et al. Disease severity and perinatal outcomes of pregnant patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:571-80. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000004339

- Hazari KS, Abdeldayem R, Paulose L, et al. Covid-19 infection in pregnant women in Dubai: a case-control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21:658. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-04130-8

- BahaaEldin H, El Sood HA, Samy S, et al. COVID-19 outcomes among pregnant and nonpregnant women at reproductive age in Egypt. J Public Health (Oxf). 2021;43:iii12-18. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdab376

- Oncel MY, Akın IM, Kanburoglu MK, et al. A multicenter study on epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 125 newborns born to women infected with COVID-19 by Turkish Neonatal Society. Eur J Pediatr. 2021;180:733-42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-020-03767-5

- Takemoto M, Menezes MO, Andreucci CB, et al. Clinical characteristics and risk factors for mortality in obstetric patients with severe COVID-19 in Brazil: a surveillance database analysis. BJOG. 2020;127:1618-26. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.16470

- Di Toro F, Gjoka M, Di Lorenzo G, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on maternal and neonatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27:36-46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2020.10.007

- Lassi ZS, Ana A, Das JK, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of data on pregnant women with confirmed COVID-19: clinical presentation, and pregnancy and perinatal outcomes based on COVID-19 severity. J Glob Health. 2021;11:05018. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.11.05018

- Andrikopoulou M, Madden N, Wen T, et al. Symptoms and critical illness among obstetric patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136:291-9. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000003996

- Karasu D, Kilicarslan N, Ozgunay SE, Gurbuz H. Our anesthesia experiences in COVID-19 positive patients delivering by cesarean section: a retrospective single-center cohort study. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2021;47:2659-65. https://doi.org/10.1111/jog.14852

- Akinosoglou K, Schinas G, Papageorgiou E, et al. COVID-19 in pregnancy: perinatal outcomes and complications. World J Virol. 2024;13:96573. https://doi.org/10.5501/wjv.v13.i4.96573

- Diriba K, Awulachew E, Getu E. The effect of coronavirus infection (SARS-CoV-2, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV) during pregnancy and the possibility of vertical maternal-fetal transmission: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Med Res. 2020;25:39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40001-020-00439-w

- Salem D, Katranji F, Bakdash T. COVID-19 infection in pregnant women: review of maternal and fetal outcomes. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021;152:291-8. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.13533

- Bhatia K; Group of Obstetric Anaesthetists of Lancashire, Greater Manchester and Mersey Study Collaborators. Obstetric analgesia and anaesthesia in SARS-CoV-2-positive parturients across 10 maternity units in the north-west of England: a retrospective cohort study. Anaesthesia. 2022;77:389-97. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.15672

- Chu Y, Yang J, Shi J, Zhang P, Wang X. Obesity is associated with increased severity of disease in COVID-19 pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Med Res. 2020;25:64. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40001-020-00464-9

- Ganesan R, Mahajan V, Singla K, et al. Mortality prediction of COVID-19 patients at intensive care unit admission. Cureus. 2021;13:e19690. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.19690

- Özer B, Arslan Yıldız Ü, Kavaklı AS, Cengiz M, Temel H, Yılmaz M. Factors affecting mortality in COVID-19. Turk J Intensive Care. 2025;23:38-52. https://doi.org/10.4274/tybd.galenos.2024.50469

- Li Y, Li H, Song C, et al. Early prediction of disease progression in patients with severe COVID-19 using c-reactive protein to albumin ratio. Dis Markers. 2021;2021:6304189. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6304189

- Macfarlane AJR, Harrop-Griffiths W, Pawa A. Regional anaesthesia and COVID-19: first choice at last? Br J Anaesth. 2020;125:243-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2020.05.016

- Dashraath P, Wong JLJ, Lim MXK, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222:521-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2020.03.021

- Goudarzi S, Firouzabadi FD, Mahmoudzadeh F, Aminimoghaddam S. Pulmonary embolism in pregnancy with COVID-19 infection: a case report. Clin Case Rep. 2021;9:1882-6. https://doi.org/10.1002/ccr3.3709

- Pecks U, Mand N, Kolben T, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy-an analysis of clinical data from Germany and Austria from the CRONOS registry. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2022;119:588-94. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.m2022.0266

Copyright and license

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is properly cited.